I don’t like to negotiate with people that I can’t beat up

Imagine a market for highly sought-after items in which the makers and sellers work hard to ensure that the items go only to certain buyers, even if other buyers might be willing to pay more. The favored buyers are then expected not to resell the items for many years, even if the values skyrocket. Ideally, in fact, the buyers are expected to give these items away eventually, for the public good. And if the buyers don’t abide by these expectations, they risk being cut off, cast out with the other unwashed wealthy who can afford to buy but have no access.

At least according to Craig Robins, a prominent Miami art collector and real estate developer who filed a federal lawsuit on March 29 in Manhattan, this is a portrait of the workings of the primary market for contemporary art, which, despite the recession, remains immense and highly competitive.

At its heart, the $8 million suit is a fairly ordinary contract dispute about confidentiality agreements and sales promises. But the details of the disagreement have provided a rare view into a normally very private world of high-end art selling in which membership rules, responsibilities, rewards and reprisals can be so complex and changeable that even art world veterans say they sometimes struggle to decode them.

{ NYTimes | Continue reading }

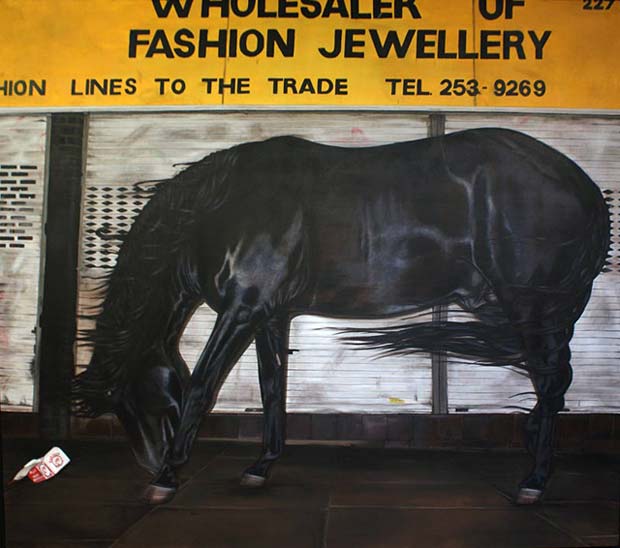

Days after the sabotage, one of his best-known older pieces, a suspended, taxidermised horse titled The Ballad of Trotsky, was auctioned in New York for $2.1m (£1.15m). Cattelan claims he won’t get a penny of that money - he sold the horse in 1996 for $5,000. Still, what is it like knowing your work is worth so much? “It’s like going to sleep 14 years old and waking up 30,” he says. “Things that maybe seemed a joke before are now taken more seriously.”

related { The Strange caase of Maurizio Cattelan | The Economics }

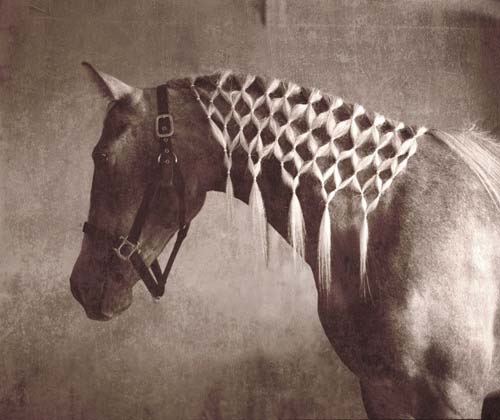

photo { unsourced | via Willie }