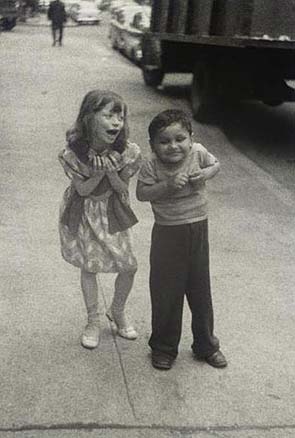

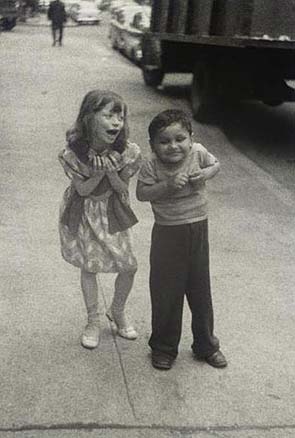

Gaze direction affects judgements of facial attractiveness

Much is known about the attractiveness of physical attributes, such as symmetry and averageness. Here we examine the effect of a social cue, eye-gaze direction, on facial attractiveness. Given that direct gaze signals social engagement, we predicted that faces showing direct gaze would be preferred to faces showing averted gaze.

Thirty-two males completed two tasks designed to assess preferences for female faces displaying a neutral expression. Participants were more likely to select the face with direct gaze, when choosing the more attractive face from direct- and averted-gaze versions of the same face.

This direct-gaze preference was stronger for high-attractive than low-attractive face sets, but was present for both. Attractiveness ratings were also higher for faces with direct than averted gaze. Interestingly, stimulus inversion weakened the preference for inverted faces, which suggests the preference does not simply reflect a bilateral symmetry bias.

{ Visual Cognition/InformaWorld }

Gaze bias: Selective encoding and liking effects

People look longer at things that they choose than things they do not choose. How much of this tendency—the gaze bias effect—is due to a liking effect compared to the information encoding aspect of the decision-making process? (…)

Colour content (whether a photograph was colour or black-and-white), not decision type, influenced the gaze bias effect in the older/newer decisions because colour is a relevant feature for such decisions. These interactions appear early in the eye movement record, indicating that gaze bias is influenced during information encoding.

{ Visual Cognition/InformaWorld }

photo { Morad Bouchakour }

eyes, science | May 12th, 2010 4:56 am

The perception and recognition of faces is crucial for the social situations we encounter every day. From the moment we are born, we prefer looking at faces than at inanimate objects, because the brain is geared to perceive them, and has specialized mechanisms for doing so. Such is the importance of the face to everyday life, that we see faces everywhere, even when they are not there.

We know that the ability to recognize faces varies among individuals. Some people are born with prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces, and others acquire the condition as a result of brain damage. At the other end of the scale are people who never forget a face - the so-called “super-recognizers”. Two independent studies published recently now provide strong evidence that the ability to recognize faces is largely inherited, and that it is passed on independently from intelligence and other cognitive functions.

{ Neurophilosophy/ScienceBlogs | Continue reading }

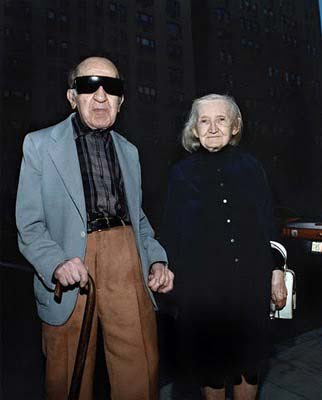

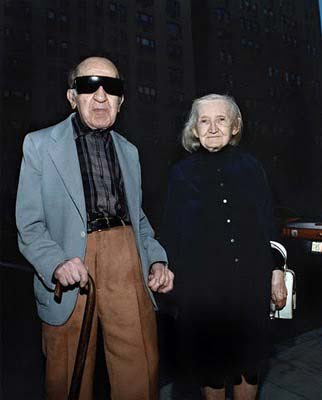

photo { Diane Arbus, NYC, 1960 }

eyes, genes, science | March 4th, 2010 6:24 pm

It starts with a barely perceptible blurring of vision from time to time - the sort of thing you might chalk up to getting older. But when you get it checked out, there is disturbing news: you have a disease called age-related macular degeneration, or AMD. (…)

People typically develop AMD after the age of 50, and it affects nearly 1 in 10 of those over the age of 80. It is the most common cause of blindness in the west.

It can progress slowly or quickly, but there is no cure. (…)

Now, however, a possible treatment for dry AMD is on the horizon.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

eyes, science | February 25th, 2010 8:30 pm

The brain processes fearful faces more quickly when seen out of the corner of the eye than when viewed straight on. Dimitri Bayle and colleagues, who made their finding using magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain scanning, believe this bias has probably evolved because threats are more likely to come from side-on.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

eyes, psychology, science | January 21st, 2010 8:16 pm

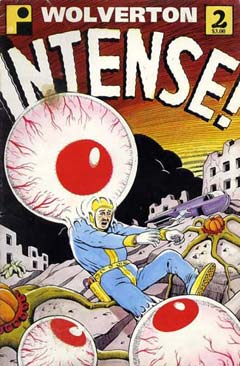

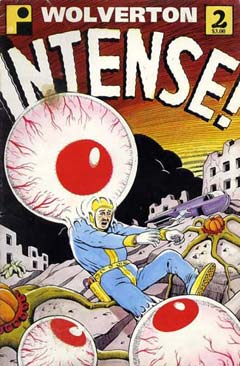

I also learned of Kandinsky’s growing love affair with the circle. The circle, he wrote, is “the most modest form, but asserts itself unconditionally.” It is “simultaneously stable and unstable,” “loud and soft,” “a single tension that carries countless tensions within it.” (…)

Quirkily enough, the artist’s life followed a circular form: He was born in December 1866, and he died the same month in 1944. This being December, I’d like to honor Kandinsky through his favorite geometry, by celebrating the circle and giving a cheer for the sphere. Life as we know it must be lived in the round, and the natural world abounds in circular objects at every scale we can scan. Let a heavenly body get big enough for gravity to weigh in, and you will have yourself a ball. Stars are giant, usually symmetrical balls of radiant gas, while the definition of both a planet like Jupiter and a plutoid like Pluto is a celestial object orbiting a star that is itself massive enough to be largely round.

On a more down-to-earth level, eyeballs live up to their name by being as round as marbles, and, like Jonathan Swift’s ditty about fleas upon fleas, those soulful orbs are inscribed with circular irises that in turn are pierced by circular pupils. Or think of the curved human breast and its bull’s-eye areola and nipple.

{ Natalie Angier/NY Times | Continue reading }

art, eyes, ideas | January 14th, 2010 6:10 pm

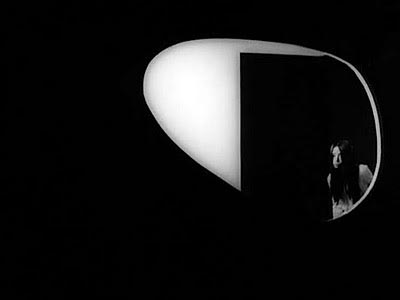

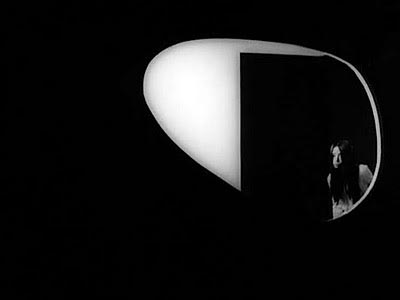

Show one image exclusively to one eye and a different image exclusively to the other eye and rather than experiencing a merging of the images, an observer’s percept will flit backwards and forwards randomly and endlessly between the two. This “binocular rivalry”, as it’s known, has been of particular interest to psychologists because it shows how the same incoming sensory information can give rise to two very different conscious experiences.

Now, in a research first, psychologists have shown that a similar process occurs with our sense of smell. If one odour is presented to one nostril and another odour is presented to the other nostril, a person will experience “binaral rivalry” - sensing one smell and then the other, backwards and forwards, rather than a blending of the two.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

From Proust’s Madeleines to the overbearing food critic in the movie Ratatouille who’s transported back to his childhood at the aroma of stew, artists have long been aware that some odors can spontaneously evoke strong memories. Scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science have now revealed the scientific basis of this connection. (…)

The key might not necessarily lie in childhood, but rather in the first time a smell is encountered in the context of a particular object or event. In other words, the initial association of a smell with an experience will somehow leave a unique and lasting impression in the brain.

{ Weizmann Institute of Science | Continue reading }

eyes, science | December 10th, 2009 7:26 pm

You’re mugged by a man with a patch over one eye. You describe him and his distinctive appearance to the police. They locate a one-eyed suspect and present him to you in a video line-up with five innocent “foils”. If this suspect is the only person in the line-up with one eye, prior research shows you’re highly likely to pick him out even if, in all other respects, he actually bears little resemblance to your mugger. So the challenge is: How to make police line-ups fairer for suspects who have an unusual distinguishing feature?

Police in the USA and UK currently use two strategies - one is to conceal the suspect’s distinguishing feature (and tell the witness they’ve done so); the other is to use make-up, theatrical props or Photoshop to adorn the other members of the line-up with the same distinctive feature. Now Theodora Zarkadi and her colleagues have compared both approaches and found the fairer method is to replicate the unusual feature.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

eyes, psychology | December 3rd, 2009 8:50 pm

The crocodilian has three eyelids. The top and bottom lids are the normal, opaque eyelids found on most reptiles and mammals. A third, transparent eyelid moves sideways across the eye. This eyelid protects the otherwise ‘open’ eyes when the crocodilian submerges and attacks under water.

Although nobody is quite sure how well the crocodile can see underwater, the transparent membrane which covers the eye during diving ensures that light can reach the eye if the water is clear enough to see. It is possible that the membrane itself alters the refractive index of light entering the eye to possibly improve vision underwater slightly.

{ Crocodile: Evolution’s Greatest Survivor by Lynne Kelly | Continue reading | Video shows an Australian saltwater crocodile opening its eye }

animals, eyes | November 7th, 2009 3:05 pm