Life as the product of life

Scientists have now accurately predicted almost the whole genome of an unborn child by sequencing DNA from the mother’s blood and DNA from the father’s saliva.

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Red White, 1961 }

Scientists have now accurately predicted almost the whole genome of an unborn child by sequencing DNA from the mother’s blood and DNA from the father’s saliva.

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Red White, 1961 }

The way that children reason about the world, there’s a lot of good evidence to suggest that there are domains of knowledge: physical, reasoning about the physical world; biological, reasoning about the living world; and reasoning about the psychological world. Those three domains are the physics, the biology and the psychology, and are deemed to cover the majority of what we do when we’re thinking about concepts. […]

This is work I’ve done with Paul Bloom. We initially started looking at sentimental objects, the emergence of this bizarre behavior that you find in children in the West. They form these emotional attachments to blankets and teddy bears and it initially starts off as an associative learning type of situation where they need to self-soothe, because in the West we typically separate children, for sleeping purposes, between one and two years of age. In the Far East they don’t, they keep children well into middle childhood, so they don’t have as much attachment object behavior. It’s common, about three out of four children start off with this sort of attachment to particular objects and then it dissipates and disappears.

What Paul and I are interested in is whether or not it was the physical properties of the object or if there was something about the identity or the authenticity of the object which is important. We embarked on a series of studies where we convinced children we had a duplicating machine, and basically we used conjuring tricks to convince the child that we could duplicate any physical object. We have these boxes which looked very scientific, with wires and lights, and we place an object in one, and activate it, and after a few seconds the other box would appear to start up by itself and you open it up and you see you’ve got two identical objects. The child spontaneously said, “Oh, it’s like a copying machine.” It’s like a photocopier for objects, if you like. Once they’re in the mindset this thing can copy, we then test what you can get away with. They’re quite happy to have their objects, their toys copied, but when it comes to a sentimental object like a blanket or a teddy bear, then they’re much more resistant to accepting the duplicate. […]

Also, we’re getting into the territory of authenticity and identity. There are some fairly old philosophical issues about what confers identity and uniqueness, and these are the principles, quiddity and haecceity. I hadn’t even heard of these issues until I started to research into it, and it turns out these obscure terms come from the philosopher Duns Scotus. Quiddity is the invisible properties, the essence shared by members of a group, so that would be the ‘dogginess’ of all dogs. But the haecceity is the unique property of the individual, so that would be Fido’s haecceity or Fido’s essence, which makes Fido distinct to another dog, for example.

These are not real properties. These are psychological constructs, and I think the reason that people generate these constructs is that when they invest some emotional time or effort into an object, or it has some significance towards them, then they imbue it with this property, which makes it irreplaceable, you can’t duplicate it. […]

The sense of personal identity, this is where we’ve been doing experimental work showing the importance that we place upon episodic memories, autobiographical memories. […] As we all know, memory is notoriously fallible. It’s not cast in stone. It’s not something that is stable. It’s constantly reshaping itself. So the fact that we have a multitude of unconscious processes which are generating this coherence of consciousness, which is the I experience, and the truth that our memories are very selective and ultimately corruptible, we tend to remember things which fit with our general characterization of what our self is. We tend to ignore all the information that is inconsistent. We have all these attribution biases. We have cognitive dissonance. The very thing psychology keeps telling us, that we have all these unconscious mechanisms that reframe information, to fit with a coherent story, then both the “I” and the “me”, to all intents and purposes, are generated narratives.

photo { Todd Fisher }

The hypothesis was that people who used particular basic word orders would have more children. Testing this hypothesis directly, basic word order is a significant predictor of the number of children a person has (linear regression, controlling for age, sex, if the person was married, if they were employed their level of education and religion, t-value for basic word order = -18.179, p < 0.00001, model predicts 36% of the variance).

It turns out that speakers of SOV languages have more children than speakers of SVO languages, while speakers with no dominant order have the fewest children on average.

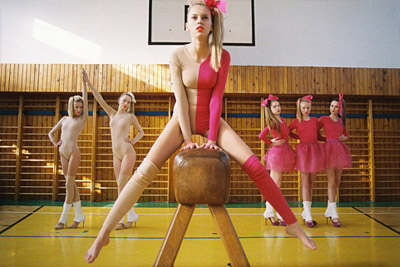

photo { Michal Pudelka }

As you know, the latest generation with a formal name is “The Millennials,” and they are basically the worst, continuing the grand tradition of every new generation being the worst.

photo { Richard Avedon | Murals and Portraits at Gagosian, until July 6, 2012 }

Researchers have shown that by becoming carnivores, our ancestors were able to give birth to a greater number of offspring.

“Eating meat enabled the breast-feeding periods to be reduced and thereby the time between births to be shortened,” said lead author Elia Psouni from Lund University in Sweden. “This must have had a crucial impact on human evolution.”

Past research has tried to explain the relatively short breast-feeding period of humans based on social and behavioral theories of parenting and family size. For an average human baby, the duration of breast-feeding is two years and four months. This is not long in relation to the maximum lifespan of our species - around 120 years. It is even less if compared to our closest relatives - female chimpanzees suckle their young for four to five years, whereas the maximum lifespan for chimpanzees is only 60 years.

When it comes to diagnosing depression in teens, differentiating mental illness from normal mood swings can be difficult. But it can be a crucial diagnosis, given that untreated depression in youth makes them more vulnerable to later substance abuse, social maladjustment, physical illness and suicide.

“Depression in adolescents affects basically every component of their thinking and makes everything very difficult psychologically and socially,” says Eva Redei, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Currently, a depression diagnosis in teens relies on their descriptions of symptoms and their physician’s subjective observations. But now a new study suggests there may be a surer, more objective way: a blood test that identifies major depression by looking for a specific set of genetic markers in the blood.

I have heard that higher IQ people tend to have less children in modern times than lower IQ people. And if larger family size makes the offspring less capable, than we are pioneering interesting times.

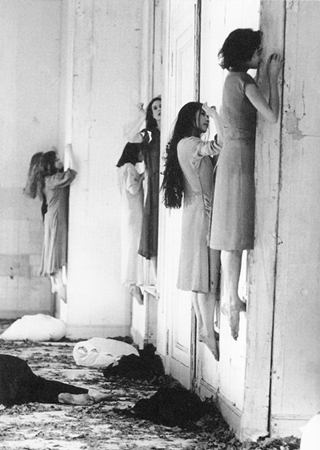

photo { Augustin Rebetez }

A birthing woman’s average labor time was barely four hours. These days, labor is a six and a half-hour marathon, at least according to a new federal study that compared almost 140,000 births from two different time periods. (…)

While the exact causes of longer labor times are unclear, the study suggests a few contributing factors, such as differences in today’s mothers from the mothers of yesteryear, namely that first-time mothers today are four years older on average, boast higher body masses, and are a more racially diverse group than their 50s-era predecessors. Babies are also bigger today, with the average newborn being 4-ounces heavier at birth than it would have been in 1960.

photo { Erwin Olaf }

Does it seem plausible that education serves (in whole or part) as a signal of ability rather than simply a means to enhance productivity? (…)

Many MIT students will be hired by consulting firms that have no use for any of these skills. Why do these consulting firms recruit at MIT, not at Hampshire College, which produces many students with no engineering or computer science skills (let alone, knowledge of signaling models)?

Why did you choose MIT over your state university that probably costs one-third as much?

photo { Robert Frank }

Family income is associated with student achievement, but careful studies show little causal connection. School factors – teacher quality, school accountability, school choice – have bigger causal impacts than family income per se, according to a new analysis by Harvard’s Program on Education Policy and Governance (PEPG).

{ EducationNext | Continue reading }

Conventional wisdom tells us that in the business world, “you are who you know” — your social background and professional networks outweigh talent when it comes to career success.

But according to a Tel Aviv University researcher, making the right connection only gets your foot in the door. Your future success is entirely up to you. (…)

When intelligence and socio-economic background are pitted directly against one another, intelligence is a more accurate predictor of future career success, he asserts.

{ American Friends of Tel Aviv University | Continue reading }

Consider what the modest justices were debating on Monday: what Americans are allowed to do AFTER they die.

Specifically, the question before the court was whether a dead man can help conceive children.

This odd point of law came before the court after a woman, Karen Capato, gave birth to twins 18 months after her husband died of cancer. She had used sperm he deposited when he was alive, and she was seeking his Social Security survivor benefits for the kids. (…)

“Let’s assume Ms. Capato remarried but used her deceased husband’s sperm to birth two children . . . ” Sotomayor posited. “Would they qualify for survivor benefits even though she is now remarried?” (…) “What if you are a sperm donor?”

Dr Benoist Schaal, researcher at the Dijon-Dresden European Laboratory for Taste and Smell (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), states that eating habits start in the womb. He explained a study conducted by himself, along with researchers Luc Marlier and Robert Soussignan, on how unborn babies “learn odours from their pregnant mother’s diet.”

The scientists asked a group of pregnant women to consume anise flavoured cookies. Once they gave birth, researchers tested their kids along with others whose mothers hadn’t consumed the cookies. They found that the former recognized the smell and showed a good disposition towards it, while the latter rejected it.

How did we end up with a drinking age of 21 in the first place?

In short, we ended up with a national minimum age of 21 because of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984. This law basically told states that they had to enact a minimum drinking age of 21 or lose up to ten percent of their federal highway funding. Since that’s serious coin, the states jumped into line fairly quickly. Interestingly, this law doesn’t prohibit drinking per se; it merely cajoles states to outlaw purchase and public possession by people under 21. Exceptions include possession (and presumably drinking) for religious practices, while in the company of parents, spouses, or guardians who are over 21, medical uses, and during the course of legal employment.

photo { Miss Aniela }

What’s happened to depictions of nature in children’s picture books?

A group of researchers led by University of Nebraska-Lincoln sociologist J. Allen Williams Jr. studied the winners of the American Library Association’s prestigious Caldecott Medal between 1938 (the year the prize was first awarded) through 2008. They looked at more than 8,000 images in the 296 volumes, and found decreasing depictions of nature and animals. (…)

Specifically, they find images of built and natural environments were “almost equally likely to be present” in books published from the late 1930s through the 1960s. But in the mid-1970s, illustrations of the built environment started to increase in number, while there were fewer and fewer featuring the natural environment.

Nurturing a child early in life may help him or her develop a larger hippocampus, the brain region important for learning, memory and stress responses, a new study shows.

Previous animal research showed that early maternal support has a positive effect on a young rat’s hippocampal growth, production of brain cells and ability to deal with stress. Studies in human children, on the other hand, found a connection between early social experiences and the volume of the amygdala, which helps regulate the processing and memory of emotional reactions. Numerous studies also have found that children raised in a nurturing environment typically do better in school and are more emotionally developed than their non-nurtured peers.

Brain images have now revealed that a mother’s love physically affects the volume of her child’s hippocampus. In the study, children of nurturing mothers had hippocampal volumes 10 percent larger than children whose mothers were not as nurturing. Research has suggested a link between a larger hippocampus and better memory.

photo { Jeanne Buechi }

We now have the potential to banish the genes that kill us, that make us susceptible to cancer, heart disease, depression, addictions and obesity, and to select those that may make us healthier, stronger, more intelligent. (…)

During that year, fertility clinics across the country have begun to take advantage of the technology’s latest tools. They are sending cells from embryos conceived here through in vitro fertilization (IVF) to private U.S. labs equipped to test them rapidly for an ever-growing list of genetic disorders that couples hope to avoid.

Recent breakthroughs have made it possible to scan every chromosome in a single embryonic cell, to test for genes involved in hundreds of “conditions,” some of which are clearly life-threatening while others are less dramatic and less certain – unlikely to strike until adulthood if they strike at all.

And science is far from finished. On the horizon are DNA microchips able to analyze more than a thousand traits at once, those linked not just to a child’s health but to enhancements – genes that influence height, intelligence, hair, skin and eye color and athletic ability.

photo { Loretta Lux }

Brooke Greenberg (born January 8, 1993), is an American from Reisterstown, Maryland, who has remained physically and cognitively similar to a toddler, despite her increasing age. She is about 30 inches (76 cm) tall, weighs about 16 pounds (7.3 kg), and has an estimated mental age of nine months to one year. Brooke’s doctors have termed her condition Syndrome X.