genes

From biology class to “C.S.I.,” we are told again and again that our genome is at the heart of our identity. Read the sequences in the chromosomes of a single cell, and learn everything about a person’s genetic information.

But scientists are discovering that […] it’s quite common for an individual to have multiple genomes. Some people, for example, have groups of cells with mutations that are not found in the rest of the body. Some have genomes that came from other people. […]

In 1953, a British woman donated a pint of blood. It turned out that some of her blood was Type O and some was Type A. The scientists who studied her concluded that she had acquired some of her blood from her twin brother in the womb, including his genomes in his blood cells.

Chimerism, as such conditions came to be known, seemed for many years to be a rarity. But “it can be commoner than we realized,” said Dr. Linda Randolph, a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles.

Twins can end up with a mixed supply of blood when they get nutrients in the womb through the same set of blood vessels. In other cases, two fertilized eggs may fuse together. […] Women can also gain genomes from their children. After a baby is born, it may leave some fetal cells behind in its mother’s body, where they can travel to different organs and be absorbed into those tissues. […] In 2012, Canadian scientists performed autopsies on the brains of 59 women. They found neurons with Y chromosomes in 63 percent of them. The neurons likely developed from cells originating in their sons. […]

Medical researchers aren’t the only scientists interested in our multitudes of personal genomes. […] Last year, for example, forensic scientists at the Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory Division described how a saliva sample and a sperm sample from the same suspect in a sexual assault case didn’t match.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

genes | September 20th, 2013 8:29 pm

First Genetic Evidence That Humans Choose Friends With Similar DNA

The discovery that friends are as genetically similar as fourth cousins has huge implications for our understanding of human evolution, say biologists.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

genes, relationships | September 20th, 2013 1:38 pm

The sense of smell is one of our most powerful connections to the physical world. Our noses contain hundreds of different scent receptors that allow us to distinguish between odours. When you smell a rose or a pot of beef stew, the brain is responding to scent molecules that have wafted into your nose and locked on to these receptors. Only certain molecules fit specific receptors, and when they slot together, like a key in a lock, this triggers changes in cells. In the case of scent receptors, specialised neurons send messages to the brain so we know what we have sniffed. […]

In the last ten years, however, reports have trickled in from bemused biologists that these receptors, as well as similar ones usually found on taste buds, crop up all over our bodies.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

genes, olfaction | July 16th, 2013 1:57 pm

High-resolution mapping of the epigenome has discovered unique patterns that emerge during the generation of brain circuitry in childhood.

While the ‘genome’ can be thought of as the instruction manual that contains the blueprints (genes) for all of the components of our cells and our body, the ‘epigenome’ can be thought of as an additional layer of information on top of our genes that change the way they are used. […]

The frontal cortex is made up of distinct types of cells, such as neurons and glia, which each perform very different functions. However, we know that these distinct types of cells in the brain all contain the same genome sequence; the A, C, G and T ‘letters’ of the DNA code that provides the instructions to build the cell; so how can they each have such different identities?

The answer lies in a secondary layer of information that is written on top of the DNA of the genome, referred to as the ‘epigenome’. One component of the epigenome, called DNA methylation, consists of small chemical tags that are placed upon some of the C letters in the genome. These tags alert the cell to treat the tagged DNA differently and change the way it is read, for example causing a nearby gene to be turned off.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Ren-Hang }

genes | July 8th, 2013 8:02 am

In August 2009, scientists in Israel raised serious doubts concerning the use of DNA by law enforcement as the ultimate method of identification. In a paper published in the journal Forensic Science International: Genetics, the Israeli researchers demonstrated that it is possible to manufacture DNA in a laboratory, thus falsifying DNA evidence. The scientists fabricated saliva and blood samples, which originally contained DNA from a person other than the supposed donor of the blood and saliva.

The researchers also showed that, using a DNA database, it is possible to take information from a profile and manufacture DNA to match it, and that this can be done without access to any actual DNA from the person whose DNA they are duplicating. The synthetic DNA oligos required for the procedure are common in molecular laboratories.

The New York Times quoted the lead author on the paper, Dr. Daniel Frumkin, saying, “You can just engineer a crime scene… any biology undergraduate could perform this.”

Dr. Frumkin perfected a test that can differentiate real DNA samples from fake ones. His test detects epigenetic modifications, in particular, DNA methylation. Seventy percent of the DNA in any human genome is methylated, meaning it contains methyl group modifications within a CpG dinucleotide context. Methylation at the promoter region is associated with gene silencing. The synthetic DNA lacks this epigenetic modification, which allows the test to distinguish manufactured DNA from original, genuine, DNA.

It is unknown how many police departments, if any, currently use the test. No police lab has publicly announced that it is using the new test to verify DNA results.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

crime, genes | June 30th, 2013 1:23 pm

blood, genes | June 30th, 2013 1:23 pm

The US Supreme Court today ruled that Myriad, the US biotech company that holds a monopoly on testing for a set of breast-cancer related genes, can’t hold a patent on genetic material. But after the news broke, Myriad’s stock shot up.

Here’s why: […] While the court ruled that a gene in its natural state is something that can’t be owned—even if it’s been isolated, which Myriad argued warranted a patent—it also ruled that complementary DNA, or cDNA, could be proprietary. Created artificially in the lab, the cDNA version of the BRCA genes lack so-called “junk” DNA, the pieces that don’t contribute to the gene’s production of proteins. This technical difference, according to the ruling, makes the genes unique enough to be distinguished legally from their natural cousins.

{ Quartz | Continue reading | Washington Post }

economics, genes, health | June 13th, 2013 1:22 pm

Certain traits, like height and hair color can largely be explained through simple genetics: If both of your parents are tall with blond hair, chances are you will be too. However, not all genes are created equal and most traits are not controlled by a single gene. Instead, most traits, such as metabolism, personality, intelligence, and even many diseases, are much more complex and rely on the interactions of hundreds of different genes. The complexity doesn’t stop there. If it did, then identical twins would be exactly the same; but they are not. Although they tend to be extremely similar, identical twins can still differ greatly in health and personality. This is because, although they carry an identical set of genes, their genes may be expressed at different levels. Genes are not simply turned “on” or “off” like a light switch, but instead function more like a dimmer switch with a dynamic range of expression. The amount that a gene is expressed can differ from one person (or twin) to another and can even fluctuate within a single individual. The mechanisms by which these kinds of changes take place are extremely complicated and are influenced by a variety of factors including one’s internal and external environment. Epigenetics is the study of these kinds of changes and the mechanisms behind them.

{ Knowing Neurons | Continue reading }

photo { Berenice Abbott, Static Electricity, c1950 }

genes | June 13th, 2013 10:58 am

For the first time, researchers have found that stress can leave an epigenetic mark on sperm, which then alters the offspring’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a part of the brain that deals with responding to stress. […]

The experiment was conducted with preadolescent and adult male mice. […]

“These findings suggest one way in which paternal-stress exposure may be linked to such neuropsychiatric diseases.”

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

genes, neurosciences, sex-oriented | June 13th, 2013 10:42 am

Every cell in our bodies runs on a 24-hour clock, tuned to the night-day, light-dark cycles that have ruled us since the dawn of humanity. The brain acts as timekeeper, keeping the cellular clock in sync with the outside world so that it can govern our appetites, sleep, moods, and much more.

But new research shows that the clock may be broken in the brains of people with depression—even at the level of the gene activity inside their brain cells.

It’s the first direct evidence of altered circadian rhythms in the brain of people with depression, and shows that they operate out of sync with the usual ingrained daily cycle. […]

In severely depressed patients, the circadian clock was so disrupted that a patient’s “day” pattern of gene activity could look like a “night” pattern—and vice versa.

{ Futurity | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

genes, neurosciences, psychology | May 17th, 2013 4:13 am

The kings of the Spanish Habsburg dynasty (1516–1700) frequently married close relatives in such a way that uncle-niece, first cousins and other consanguineous unions were prevalent in that dynasty. In the historical literature, it has been suggested that inbreeding was a major cause responsible for the extinction of the dynasty when the king Charles II, physically and mentally disabled, died in 1700 and no children were born from his two marriages, but this hypothesis has not been examined from a genetic perspective. In this article, this hypothesis is checked by computing the inbreeding coefficient (F) of the Spanish Habsburg kings from an extended pedigree up to 16 generations in depth and involving more than 3,000 individuals. […]

It is speculated that the simultaneous occurrence in Charles II of two different genetic disorders […] could explain most of the complex clinical profile of this king, including his impotence/infertility which in last instance led to the extinction of the dynasty.

{ PLoS | Continue reading | Read more: Nature }

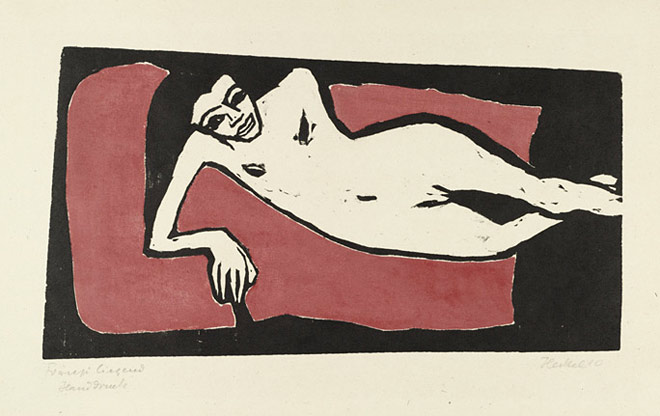

photo { Erich Heckel, Fränzi Reclining, 1910 }

flashback, genes | April 21st, 2013 11:51 am

XYY syndrome is an aneuploidy (abnormal number) of the sex chromosomes in which a human male receives an extra Y-chromosome.

Some medical geneticists question whether the term “syndrome” is appropriate for this condition because its clinical phenotype is normal and the vast majority (an estimated 97% in Britain) of 47,XYY males do not know their karyotype.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Triple X syndrome is a form of chromosomal variation characterized by the presence of an extra X chromosome in each cell of a human female. The condition occurs only in females. […]

Because of the lyonization, inactivation, and formation of a Barr body in all female cells, only one X chromosome is active at any time. Thus, Triple X syndrome most often has only mild effects, or has no unusual effects at all.

Symptoms may include tall stature; small head (microcephaly); vertical skinfolds that may cover the inner corners of the eyes (epicanthal folds); delayed development of certain motor skills, speech and language; learning disabilities, such as dyslexia; or weak muscle tone.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Klinefelter syndrome, or XXY syndrome, is a genetic disorder in which there is at least one extra X chromosome to a standard human male karyotype, for a total of 47 chromosomes rather than the 46 found in genetically normal humans. […]

This chromosome constitution exists in roughly between 1:500 to 1:1000 live male births but many of these people may not show symptoms. […]

Affected males are often infertile, or may have reduced fertility. […] XXY males are also more likely than other men to have certain health problems, which typically affect females, such as breast cancer and osteoporosis.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photos { Frieke Janssens }

genders, genes | March 21st, 2013 2:38 pm

Prevailing wisdom suggests that our genes remain largely fixed over time. But, an emerging field of research is beginning to prove this intuition wrong. Scientists are uncovering increasing evidence that changes in the expression of hundreds of genes can occur as a result of the social environments we inhabit. As a result of these dynamics, experiences we have today can affect our health for days and even months into the future. […]

People who experience chronic social isolation show reduced antiviral immune response gene activity, which leaves them vulnerable to viral infections like the common cold. […] Other social conditions that have been found to influence human gene expression include being socially evaluated or rejected, which can have different consequences for different people depending on their sensitivity to social threat.

{ APS | Continue reading }

photo { Jonathan Waiter }

genes, health, relationships | March 20th, 2013 10:43 am

What your mother ate around your conception could have affected your genes, or at least how they function, by switching certain genes on and off through DNA methylation. […]

People in rural parts of the Gambia have dramatic seasonal changes in their diet, because crops are planted at the beginning of the rainy season and harvested at the end, as there is no irrigation the rest of the year. […]

In a paper published in PLoS Genetics, the children conceived in August and September, the peak of the rainy season when nutrition is poor, had higher levels of DNA methylation in five genes, which surprised the researchers, as they had expected lower levels. These included the SLITRK1 gene associated with Tourette’s syndrome, and the PAX8 gene linked to hypothyroidism.

{ Genome Engineering | Continue reading }

photo { Marianna Rothen }

food, drinks, restaurants, genes, kids | March 14th, 2013 11:27 am

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of an existing or previously existing human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning; human clones in the form of identical twins are commonplace, with their cloning occurring during the natural process of reproduction. There are two commonly discussed types of human cloning: therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning involves cloning adult cells for use in medicine and is an active area of research. Reproductive cloning would involve making cloned humans. A third type of cloning called replacement cloning is a theoretical possibility, and would be a combination of therapeutic and reproductive cloning. Replacement cloning would entail the replacement of an extensively damaged, failed, or failing body through cloning followed by whole or partial brain transplant.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

The biodesign movement builds on ideas in Janine Benyus’ trailblazing 1997 book Biomimicry, which urges designers to look to nature for inspiration. But instead of copying living things biodesigners make use of them. […]

Alberto Estévez, an architect based in Barcelona, wants to replace streetlights with glowing trees created by inserting a bioluminescent jellyfish gene into the plants’ DNA.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

The most radical figure in the biodesign movement is Eduardo Kac, who doesn’t merely incorporate existing living things in his artworks—he tries to create new life-forms. “Transgenic art,” he calls it.

There was Alba, an albino bunny that glowed green under a black light. Kac had commissioned scientists in France to insert a fluorescent protein from Aequoria victoria, a bioluminescent jellyfish, into a rabbit egg. The startling creature, born in 2000, was not publicly exhibited, but the announcement caused a stir, with some scientists and animal rights activists suggesting it was unethical. […] Then came Edunia, a petunia that harbors one of Kac’s own genes.

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

art, genes, science | February 22nd, 2013 1:42 pm

Researchers have in recent years come to realize that genes aren’t a fixed, predetermined program simply passed from one generation to the next. Instead, genes can be turned on and off by experiences and environment. What we eat, how much stress we undergo, and what toxins we’re exposed to can all alter the genetic legacy we pass on to our children and even grandchildren. In this new science of ”epigenetics,” researchers are exploring how nature and nurture combine to cause behavior, traits, and illnesses that genes alone can’t explain, ranging from sexual orientation to autism to cancer. “We were all brought up to think the genome was it,” said Rockefeller University molecular biologist C. David Allis. “It’s really been a watershed in understanding that there is something beyond the genome.”

{ The Week | Continue reading }

genes, science | February 19th, 2013 11:18 am

There is human DNA discarded carelessly all over New York City and one artist has been picking up a little of it and making facial reconstructions of what its owner might look like.

“I’ve worked with face recognition and speech recognition algorithms in the past, but I had never considered the emerging possibility of genetic surveillance; that the very things that make us human: hair, skin, saliva, become a liability as we constantly face the possibility of shedding these traces in public space, leaving artifacts which anyone could come along and mine for information,” Heather Dewey-Hagborg, a self-described information artist, wrote in a blog post introducing the concept that she has spent about a year working on. […]

She has taken DNA samples found on the streets of New York City from cigarette butts and gums and has been able to determine gender, ethnicity (based on the mother’s side) and eye color.

{ The Blaze | Continue reading | The Boston Globe | DNA could be used to visually recreate a person’s face }

art, genes | February 10th, 2013 1:30 pm

Scientists have identified genetic circumstances under which common mutations on two genes interact in the presence of cocaine to produce a nearly eight-fold increased risk of death as a result of abusing the drug.

The variants are found in two genes that affect how dopamine modulates brain activity. Dopamine is a chemical messenger vital to the regular function of the central nervous system, and cocaine is known to block transporters in the brain from absorbing dopamine after its release.

The same dopamine genes are also targeted by medications for a number of psychiatric disorders. The researchers say that these findings could help determine how patients will respond to certain drugs based on whether they, too, have mutations that interact in ways that affect dopamine flow and signaling.

{ The Ohio State University | Continue reading }

drugs, genes | January 23rd, 2013 7:55 am

George Church, 58, is a pioneer in synthetic biology, a field whose aim is to create synthetic DNA and organisms in the laboratory. During the 1980s, the Harvard University professor of genetics helped initiate the Human Genome Project that created a map of the human genome.

SPIEGEL: Mr. Church, you predict that it will soon be possible to clone Neanderthals. What do you mean by “soon”? Will you witness the birth of a Neanderthal baby in your lifetime?

Church: That depends on a hell of a lot of things, but I think so. The reason I would consider it a possibility is that a bunch of technologies are developing faster than ever before. In particular, reading and writing DNA is now about a million times faster than seven or eight years ago. Another technology that the de-extinction of a Neanderthal would require is human cloning. We can clone all kinds of mammals, so it’s very likely that we could clone a human. […]

SPIEGEL: So let’s talk about possible benefits of a Neanderthal in this world.

Church: Well, Neanderthals might think differently than we do. We know that they had a larger cranial size. They could even be more intelligent than us. When the time comes to deal with an epidemic or getting off the planet or whatever, it’s conceivable that their way of thinking could be beneficial.

SPIEGEL: How do we have to imagine this: You raise Neanderthals in a lab, ask them to solve problems and thereby study how they think?

Church: No, you would certainly have to create a cohort, so they would have some sense of identity. They could maybe even create a new neo-Neanderthal culture and become a political force.

{ Der Spiegel | Continue reading }

genes, science | January 20th, 2013 7:18 am

A massive effort to uncover genes involved in depression has largely failed. By combing through the DNA of 34,549 volunteers, an international team of 86 scientists hoped to uncover genetic influences that affect a person’s vulnerability to depression. But the analysis turned up nothing.

The results are the latest in a string of large studies that have failed to pinpoint genetic culprits of depression. […] Depression seems to run in families, leading scientists to think that certain genes are partially behind the disorder. But so far, studies on people diagnosed with depression have failed to reveal these genes.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

genes, mystery and paranormal, psychology | January 16th, 2013 1:57 pm