I will take the sun in my mouth and leap into the ripe air, alive

For thousands of years, a core pursuit of medical science has been the careful observation of physical symptoms and signs. Through these observations, supplemented more recently by investigative techniques, an understanding of how symptoms and signs are generated by disease has developed. However, there is a group of patients with symptoms and signs that, from the earliest medical records to the present day, elude a diagnosis with a typical ‘organic’ disease. This is not simply because of an absence of pathology after sufficient investigation, rather that symptoms themselves are inconsistent with those occurring in typical disease. In times past, these symptoms were said to be ‘hysterical’, a term now replaced by the less pejorative but no more enlightening labels: ‘medically unexplained’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘conversion’, ‘non-organic’ and ‘functional’.

There are numerous historical examples of patients identified as having hysteria who would now be diagnosed with an organic medical disorder. Some have assumed that this process of salvaging patients from (mis)diagnosis with hysteria would continue inexorably until a ‘proper’ medical diagnosis was achieved. Slater (1965), in his influential paper on the topic, described the diagnosis of hysteria as ‘a disguise for ignorance and a fertile source of clinical error’. In other words, with increasing medical knowledge, all patients would be rescued from a diagnostic category that did little more than assert that they were ‘too difficult’.

This has not come to pass (Stone et al., 2005). Recent epidemiological work has demonstrated that neurologists continue to diagnose a ‘non-organic’ disorder in ∼16% of their patients, making this the second most common diagnosis of neurological outpatients.

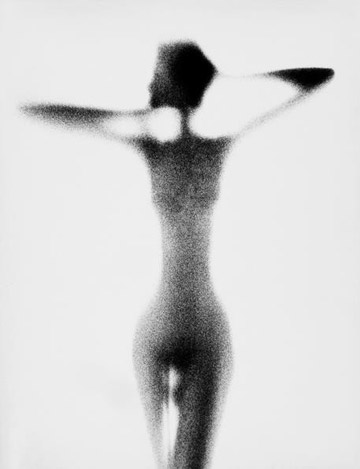

photo { Paul Himmel }