Bloom holds up his right hand on which sparkles the Koh-i-Noor diamond. His palfrey neighs. Immediate silence.

By now, the diamond thieves who pulled off a brazen $50 million heist on the tarmac of Brussels Airport are the most wanted men in Europe. They’re most likely lying low somewhere, waiting for the heat to die down. Soon enough, though, they’ll want to turn that loot into cash. But how does one actually go about fencing $50 million in stolen diamonds? In fact, it’s easier than you might think.

Clearly, these guys planned their Feb. 18 heist well — it was fast and efficient, and it employed minimal violence in intercepting the diamonds at a moment of vulnerability. Given their professionalism, it’s quite likely that they planned just as carefully what to do with the loot.

I know a little bit about what they might have been thinking, from investigating the largest diamond heist in history, the 2003 burglary of $500 million in stones in Antwerp, Belgium, by a group of Italian thieves known as the School of Turin.

Let’s assume these new crooks don’t already have someone in mind on whom they intend to unload all the diamonds. They’ll have to sell them slowly to avoid drawing attention, but that’s OK, as diamonds don’t lose value with the passage of time. The first thing to do with all those stolen diamonds is to divide them up into polished stones, rough stones, and anything in between. […] The biggest problem is getting rid of the stones’ identifying characteristics. Some of the polished diamonds will have signature marks on them, such as tiny, almost invisible, laser engravings. These can be removed. But some polished diamonds have laser-inscribed marks on their girdle, commonly used for branding purposes: Canadian diamonds often feature a maple leaf or polar bear, while De Beers uses its distinctive “Forevermark.” Such brands by themselves are not a concern; in fact, removing them might hurt the resale value of a stone. But the problem facing the thieves is that these markings often include a serial number used to identify a specific stone. […]

One thing working in the thieves’ favor is that in the complex, busy world of the gem trade, a single diamond can trade hands multiple times in a single day. And not everyone keeps clear records. By the time someone realizes that they’re in possession of a stolen stone, it could have passed through dozens of hands, leaving the trail too cold for police to be able to track it back to the original trader who bought it off the thieves.

Another thing going for the thieves is that the individual marking of stones is still rather rare. Yes, diamond-grading laboratories offer services that will inscribe a unique number on a diamond to match that polished stone to a report detailing its attributes. But it’s far more common to simply keep a diamond in a transparent, sealed, tamper-proof case along with a given report that notes cut, clarity, color, carat weight, and other details. Moreover, even the best labs don’t note or keep track of any unique identifier such as an optical fingerprint of polished stones. There are indeed services geared toward retail clients that will analyze diamonds and keep extremely detailed records for insurance or identification purposes. But these kinds of services aren’t used in Antwerp’s wholesale diamond trade. […]

The ironic thing about this week’s heist, though, is that odds are that the vast majority of these stolen stones will end up back in Antwerp soon — but the people buying and selling them will have no idea they were stolen. Even victims of this heist would be unlikely to recognize one of their stones.

related { Robbers breach gate, steal $50 million in diamonds at Belgian airport }

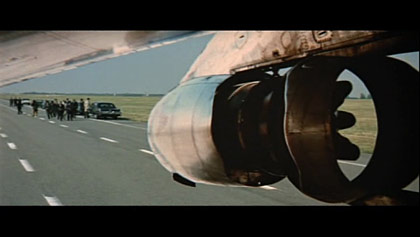

screenshot { The Sicilian Clan, 1969 | more }