Where’s my flyswatter?

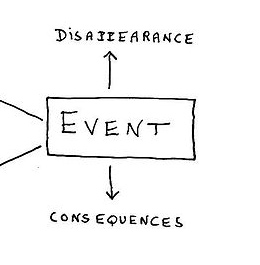

In February 2012, a number of hedge fund traders noted one particular index–CDX IG 9–that seemed to be underpriced. It seemed to be cheaper to buy credit default protection on the 125 companies that made the index by buying the index than by buying protection on the 125 companies one by one. This was an obvious short-term moneymaking opportunity: Buy the index, sell its component short, in short order either the index will rise or the components will fall in value, and then you will be able to quickly close out your position with a large profit.

But February passed, and March passed, and April rolled in, and the gap between the price of CDX IG 9 and what the hedge fund traders thought it should be grew. And their bosses asked them questions, like: “Shouldn’t this trade have converged by now?” “Have you missed something?” […]

So the hedge fund traders began asking who their counterparty was. It seemed that they all had the same counterparty. And so they began calling their counterparty “the London Whale.” They kept buying. And the London Whale kept selling. And so they had no opportunity to even begin to liquidate their positions and their mark-to-market losses grew, and the risk they had exposed their firms to grew.

So they got annoyed. And they went public, hoping that they could induce the bosses of the London Whale to force him to unwind his possession, in which case they would profit immensely not just when the value of CDX IG 9 returned to its fundamental but by price pressure as the London Whale had to find people to transact with. And so we had ‘London Whale’ Rattles Debt Market, and similar stories.

The London Whale was Bruno Iksil [a trader working for the London office of JPMorgan Chase]. He had been losing, and rolling double or nothing, and losing again for months. His boss, Ina Drew, took a look at his positions. They found they had a choice: they could hold the portfolio and thus go all-in, or they could fold. They could hold CDX IG 9 until maturity–make a fortune if a fewer-than-expected number of its 125 companies went bankrupt, and lose J.P. Morgan Chase entirely to bankruptcy if more did. Or they could take their $6 billion loss and go home. What could they do if the bet went wrong and they had to eat losses at maturity? J.P. Morgan Chase couldn’t print money. So Drew stood Iksil down, and the hedge fund traders had their happy ending.

[…]

“Why did the interest rate on the Ten-Year Treasury peak at 4%? And why has it gone down since then? And why won’t it go back to its 5%-7% fundamental.” And they looked around. And they found Ben Bernanke. The Washington Super-Whale. […] From my perspective, of course, the hedge fundies’ analogy between the London Whale and the Washington Super-Whale is all wrong.