‘No man can bring about the perfect murder. Chance, however, can do it.’ –Nabokov

Serendipity, the notion that research in one area often leads to advances in another, has been a central idea in the economics of innovation and science and technology policy. Claims about serendipity, and the futility of planning research, were central to the argument in Vannevar Bush’s Science–The Endless Frontier often considered the blueprint of post-World War II U.S. science policy. […]

The idea of serendipity has been influential not only in practice, but also in theory. Much of the economic work on the governance of research starts from the notion that basic research has economically valuable but unanticipated outcomes. Economic historians, most notably Nathan Rosenberg, have emphasized the uncertain nature of new innovations, and that many technologies (for example, the laser) have had important, but unanticipated, uses and markets. Like Vannevar Bush, prominent economists studying science policy have argued that research cannot and should not be targeted at specific goals but instead guided by the best scientific opportunities, as have influential philosophers of science. […]

[T]here is surprisingly little large-sample evidence on the magnitude of serendipity. This has contributed to perennial debate about the benefits of untargeted or fundamental research, relative to those from basic (or applied) research targeted at specific goals. […] [C]laims about serendipity have been important for diffusing calls (from Congress and taxpayers) to shift funding from fundamental research to that targeted at specific outcomes. […]

I provide evidence on the serendipity hypothesis as it has typically been articulated in the context of NIH research: that progress against specific diseases often results from unplanned research, or unexpectedly from research oriented towards different diseases. […] If the magnitudes of serendipity reported here are real, this would pose real challenges for medical research funding. If disease is not the right organizing category for NIH research, then what might be? Is it possible to mobilize taxpayer and interest group support for science that cuts across dis- eases, or is the attachment of disease categories, however fictitious, required? Even more fundamentally, serendipity makes it hard to fine tune policy to stimulate research areas that taxpayers care about (or even limit the growth of areas where there is too much innovation), and assess whether a funding agency is allocating its funds reasonably given what its patrons desire.

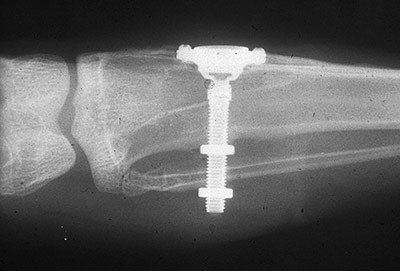

image { Radiograph of Brånemark’s initial rabbit specimen. While studying bone cells in a rabbit femur using a titanium chamber, Brånemark was unable to remove it from bone. His realization that bone would adhere to titanium led to the concept of osseointegration and the development of modern dental implants. | more }