You can always make a deal when two parties want different things. The only time you can’t make a deal is when people want exactly the same limited resource.

When we talk we take turns, where the “right” to speak flips back and forth between partners. This conversational pitter-patter is so familiar and seemingly unremarkable that we rarely remark on it. But consider the timing: On average, each turn lasts for around 2 seconds, and the typical gap between them is just 200 milliseconds—barely enough time to utter a syllable. That figure is nigh-universal. It exists across cultures, with only slight variations. It’s even there in sign-language conversations. […]

(Overlaps only happened in 17 percent of turns, typically lasted for just 100 milliseconds, and were mostly slight misfires where one speaker unexpectedly drew out their last syllable.) […]

This means that we have to start planning our responses in the middle of a partner’s turn, using everything from grammatical cues to changes in pitch. We continuously predict what the rest of a sentence will contain, while similarly building our hypothetical rejoinder, all using largely overlapping neural circuits.

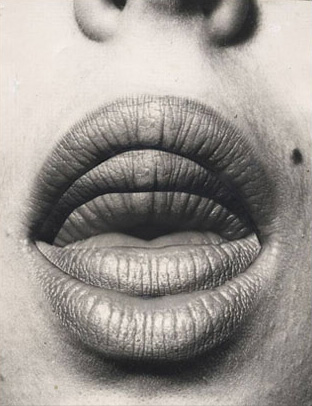

collage { Penelope Slinger, Giving You Lip, 1973 }