A poor soul gone to heaven: and on a heath beneath winking stars a fox, red reek of rapine in his fur, with merciless bright eyes scraped in the earth, listened, scraped up the earth, listened, scraped and scraped.

Project Icarus is an ambitious plan to reassess our ability to send a spacecraft to another star. But is it any more than science fiction?

Until recently, planetary geologists had only a handful of subjects to study. The discovery of exoplanets has changed all that, however. The number of known planets orbiting other stars now approaches 500 and few astronomers seriously doubt that an Earth-like body will turn up somewhere soon.

When that happens, we’ll want to study it in unprecedented detail. We’ll want to know its mass, temperature, atmospheric composition, its colour, whether it has seas and continents and if so whether these support life, perhaps even of the intelligent kind. But above all we’ll want to know whether we can visit this place.

Such a trip will not be easy but it may not be entirely impossible. In fact, rocket scientists have dreamed up various plans for interplanetary probes. One of the more famous was Project Daedalus, a 1970s plan by the British Interplanetary Society for a nuclear-powered spacecraft capable of visiting Barnard’s Star some 6 light years away within a human lifetime.

Today, the British Interplanetary Society and another organisation called the Tau Zero Foundation have posted plans on the arXiv to redesign Daedalus in the light of the 30 years of advances that have taken place since the original. The new plan is called Project Icarus. (In Greek mythology, Icarus was the son of Daedalus who died after flying too close to the Sun and melting the wax that held his wings together.)

Icarus could be an interesting measure of the progress in nuclear propulsion technology in the 30 years since Daedalus was conceived.

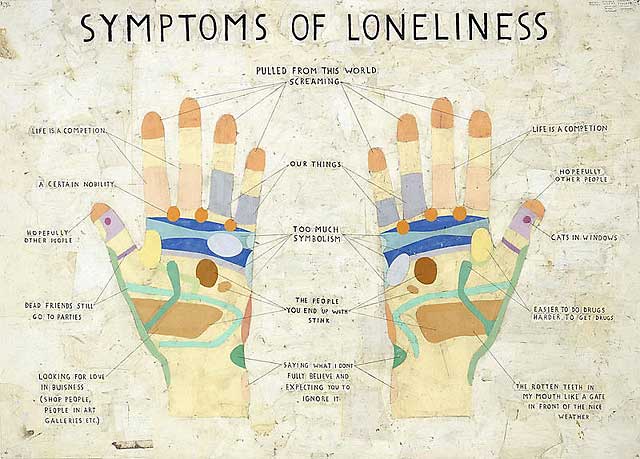

artwork { Simon Evans, Symptoms of Loneliness, 2009 | pen, paper, scotch tape, correction fluid | enlarge | more }