‘Democracy is an abuse of statistics.’ –Jorge Luis Borges

The world is more complex and less controllable than ‘rational’ planners believe. There are two main reasons for this. First, as behavioural economics tells us, agents - be they individuals, institutions or governments - do not necessarily behave rationally; their responses when confronted by new information or a different set of incentives may be hard to anticipate. Second, as the study of networks shows, our tastes and preferences can be altered directly by the behaviour of others and can change over time. Natural selection is now believed to favour social learning strategies that specify when and whom to copy. It seems that humans are particularly adept at this. (…)

In the late 1990s, a group of epidemiologists, sociologists and physicists analysed a database of individuals and their sexual contacts. The results were published in Nature, one of the world’s leading scientific journals. They found that most people have only a few sexual partners, but that a small number have hundreds or even thousands. The real originality of the paper was its finding that the structure of the pattern of the contacts closely reflected a recently discovered type of network that is described as ‘scale-free’. Such networks are important in the natural sciences, and more of them - at least, good approximations of the scale-free pattern - have been discovered in the human world. The internet, for example, has these properties. A few sites receive a massive number of hits, while most get very few. A whole industry has grown up in American marketing circles trying to find these influential ‘hubs’. (…)

Another important type of network that makes life even more complicated is the ‘small-world’ network. When we delve into the maths, there are considerable similarities between a scale-free and a small-world network. But their basic social structure is different. In the scale-free network, there are a few agents who have huge potential influence. The small world is much more like overlapping sets of ‘friends of friends’. The additional feature is that, while no one has a large number of connections, a few agents may have ‘long-range’ connections to others who are remote from their immediate cliques. However, these individuals may be even harder to identify in practice than the hubs of a scale-free network, precisely because they themselves are not distinguished by having an unusual number of connections.

{ RSA Journal | Continue reading }

The World Wide Web, with its potential to connect people globally, was paradoxically a technology that connected people locally.

{ RSA Journal | Continue reading }

Rumors of the web’s memory are greatly exaggerated.

Jeffrey Rosen has an engaging piece in the Times about privacy and the web that touches on issues of forgiveness and reputation and how the Internet has basically screwed that up for all of us; the upshot being that because your Facebook profile never really goes away, your sins are plastered on the world’s largest wall for all to see forever. Here’s the thing. They’re probably not. Forever, that is.

{ Big Questions Online | Continue reading }

As data volumes continue to grow, it’s clear that the Internet’s infrastructure needs upgrading. What’s not clear is who is going to pay for it.

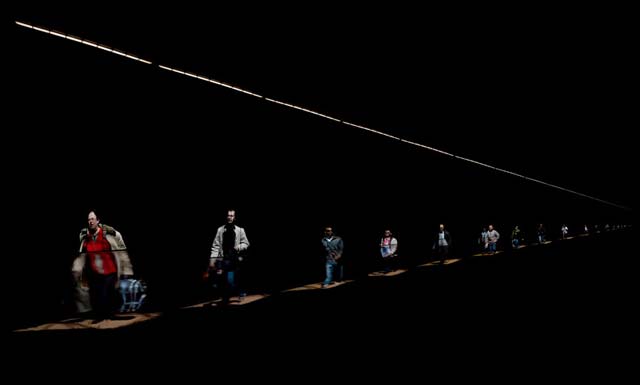

photo { Manuel Vazquez }