But the horn, the drinking, the day of dread are not now

When I was seven years old, I would sit by the window and wait for Mr. Kramer. He would show up at 4:00 every Wednesday. He wore a brown fedora and a rumpled brown suit and had a stub of an unlit cigar hanging from his mouth. He always had a great big smile on his face and, to keep the cigar from falling, he clenched it between his teeth and talked in a mumble.

He smelled like a cigar and, now that I think about it, dressed all in brown, he looked like a cigar. A fat, stubby cigar. His big belly would hang over his belt and he always perspired so that winter or summer, you could see beads of sweat on his forehead. He was a nice jolly man and, as a kid, I could never understand why my mother would make a sour face when I would shout out, “Mr. Kramer is here, Mom.”

“How are you, Mrs. Della Femina?” he would ask.

“I am fine,” she would say, deadpan. I never saw her smile in front of Mr. Kramer.

“And you,” he would say, “you little monkey. How are you doing in school?”

“I’ve got three stars already, Mr. Kramer,” I would answer proudly.

“Isn’t that great?” he would say.

While we talked, my mother would be digging into her pocketbook and most of the time she would come up with 75 cents. Sometimes she would say, “Mr. Kramer, I’m a little short this week. Is it okay if I pay you next week?”

“No problem” he would reply. But he would look serious and my Mom would look even more serious. A few seconds later he would break into a smile and say, “I’ll see you next week.” Then he would pinch my cheek and say, “Keep getting those stars, monkey, and everything will be all right.”

“I will,” I would answer, not knowing that as one gets older those stars become harder and harder to come by in life. Then he was off next door to see Adeline, my friend Andy’s mother, and collect her 75 cents.

One day I said, “I really like Mr. Kramer. Why does everybody give him money?” (Thinking to myself maybe this was a career for me. You know, you walk around with a cigar in your mouth, smile and everybody gives you money).

“Because he’s an insurance man.” (…)

At that time, my father, a good union man who voted Democrat all the way, was working at three jobs. He was a press operator at The New York Times. He sold newspapers in the Sea Beach (now the N) train station, starting at 6:00 in the morning. And he ran a ride in Coney Island from 7 PM until midnight. The three jobs brought in a total of $35. When you work three jobs to make $35 a week, 75 cents to pay for a coffin when you’re dead is a lot of money. But my mom paid. She had no choice.

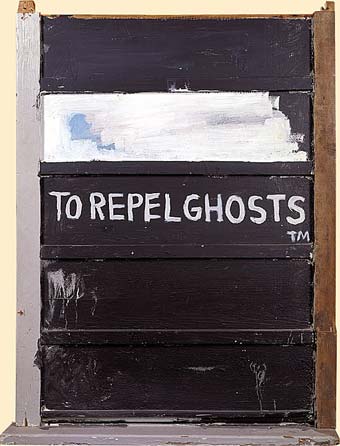

artwork { Jean-Michel Basquiat, To Repel Ghosts, 1986 }