Or the birds start their treestirm shindy. Look, there are yours off, high on high!

{ Yves Klein, Empreinte du fond d’une baignoire vide don’t l’eau avait été colorée de vermillion, COS 2, 1960 | Yves Klein Archives | Continue reading }

‘As I lay stretched upon the beach of Nice, I began to feel hatred for birds which flew back and forth across my blue sky, cloudless sky, because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work.’ –Yves Klein

Who is Yves Klein, and what’s the story behind his unearthly color? Lolling on a beach in 1947, a teenage Klein carved up the universe of art between him and two friends. Painter Arman Fernandez chose earth, Claude Pascal words, while Klein claimed the sky. (…)

Klein’s first public exhibit in 1954 featured monochrome canvases in several shades—orange, pink, yellow as well as blue—but the audience’s placid reception enraged him, as if it were “a new kind of bright, abstract interior decoration,” as Weitermeier puts it. Klein’s response was to double down exclusively on what he considered the world’s most limitless, enveloping color: blue [International Klein Blue].

With the help of Parisian paint dealer Edouard Adam, he suspended pure ultramarine pigment—the most-prized blue of the medieval period— in a synthetic resin called Rhodopas, which didn’t dull the pigment’s luminosity like traditional linseed oil suspensions. Their much-vaunted patent didn’t apply to the color proper, but rather protected Klein’s works made with the paint, which involved rolling naked ladies in the new hue and transferring their body-images to canvas.

Invitees to two simultaneous 1957 exhibits received an blue-drenched postcard in the mail, complete with an IKB postage stamp actually canceled by the French postal service (an authentic touch Klein probably bribed his postman for).

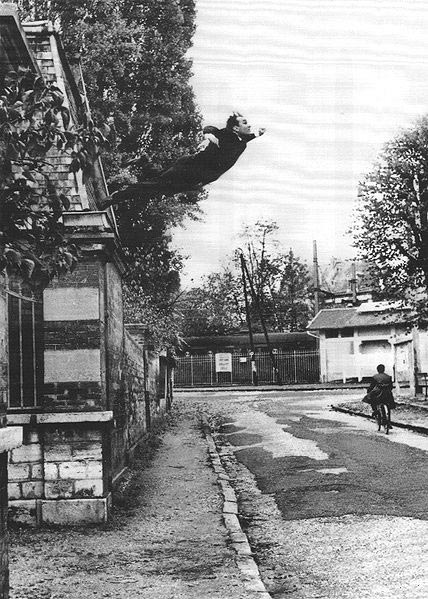

Photograph of a performance by Yves Klein at Rue Gentil-Bernard, Fontenay-aux-Roses, October 1960, by Harry Shunk

In one of the best-known photographs in art, the French artist Yves Klein projects himself confidently into space, seemingly as heavenbound as a Titian angel, while all unawares the banal figure of a cyclist goes about his earthbound business. The irony of Le saut dans le vide (Leap into the void, 1960) is that an image so faithful to Klein’s artistic quest should be a fake, a confection manufactured in the darkroom by him and the photographer who took the shot, Harry Shunk.

Klein’s performance, staged for a one-off newspaper he was planning, involved the taking of two pictures. First, Shunk photographed the street empty of all save the cyclist. Then Klein, a keen exponent of judo, climbed to the top of a wall and dived off it a dozen times — onto a pile of mats assembled by the members of his judo school across the road. The two elements were then melded to create the desired illusion.

The image, which has had a lasting influence on performance art, was expressive of Klein’s intent to explore the metaphorical void central to his work, a neutral zone free of prior prejudices. It was also a criticism of Nasa’s space travel plans, for Klein the ultimate folly of an over-materialistic world. Yet though the montage was executed under his direction, the presence of Shunk — who became a rather forgotten figure — should not be ignored.