Cause nobody is that strong

A 17-year-old boy, caught sending text messages in class, was recently sent to the vice principal’s office at Millwood High School in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The vice principal, Steve Gallagher, told the boy he needed to focus on the teacher, not his cellphone. The boy listened politely and nodded, and that’s when Mr. Gallagher noticed the student’s fingers moving on his lap.

He was texting while being reprimanded for texting.

“It was a subconscious act,” says Mr. Gallagher, who took the phone away. “Young people today are connected socially from the moment they open their eyes in the morning until they close their eyes at night. It’s compulsive.”

Because so many people in their teens and early 20s are in this constant whir of socializing—accessible to each other every minute of the day via cellphone, instant messaging and social-networking Web sites—there are a host of new questions that need to be addressed in schools, in the workplace and at home. Chief among them: How much work can “hyper-socializing” students or employees really accomplish if they are holding multiple conversations with friends via text-messaging, or are obsessively checking Facebook? (…)

While their older colleagues waste time holding meetings or engaging in long phone conversations, young people have an ability to sum things up in one-sentence text messages, Mr. Bajarin says. “They know how to optimize and prioritize. They will call or set up a meeting if it’s needed. If not, they text.” And given their vast network of online acquaintances, they discover people who can become true friends or valued business colleagues—people they wouldn’t have been able to find in the pre-Internet era.

{ Wall Street Journal | Continue reading }

In this era of media bombardment, the ability to multitask has been seen as an asset. But people who commonly have simultaneous input from several types of media—surfing the Web while texting and listening to music, for instance—may in fact find it harder to filter out extraneous information. “We embarked on the research thinking that people who multitasked must be good at it,” says Clifford Nass, a psychologist at Stanford University who studies human-computer interaction. “So we were enormously surprised.”

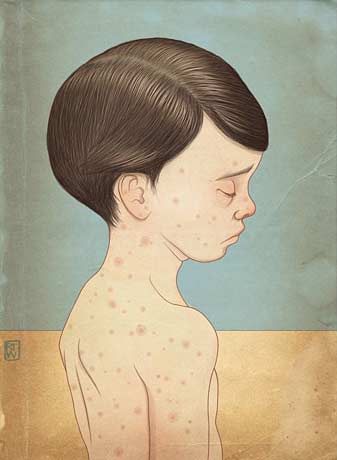

illustration { Richard Wilkinson }