‘Nobody gets justice. People only get good luck or bad luck.’ –Orson Welles

At its heart, cancer is caused when our genes – the instructions encoded in the DNA found within our cells – go wrong. Without the correct instructions, cells start to multiply out of control, fail to die when damaged, and begin to spread around the body.

Scientists studying the precise nature of these microscopic – yet potentially disastrous – errors have found all kinds of weird and wonderful mistakes. These range from very specific ‘typos’ to large scale rearrangements.

To use an analogy, if the entire DNA of a cell (its genome) is a bit like a recipe book, then some genetic faults are the equivalent of simply changing ‘tomato’ into ‘potato’, while others are akin to ripping whole pages out and shuffling them around.

But recent revolutionary research from scientists in the US and UK has revealed a completely different – and catastrophic – way for DNA to get messed up.

Published in the prestigious journal Cell, this groundbreaking work comes from the Cancer Genome Project team, who brought us the first fully mapped cancer genomes at the end of 2009. Since then they’ve been busy analysing DNA from samples taken from many different types of cancer and trying to spot interesting patterns in the data.

Since the 1970s, the prevailing view has been that cancers ‘evolve’ gradually, picking up a few new faults each time a cell divides. This idea is supported by plenty of research into cancer genomes over the years.

But in their latest investigations, the Cancer Genome team noticed a few examples that bucked this trend. (…)

Within our cells, our DNA is arranged into individual pieces known as chromosomes, and 46 chromosomes are found in virtually all human cells. If the entire DNA of a cell is analogous to an instruction manual, then chromosomes would be individual ‘chapters’.

In a few cancer samples, the scientists found that one or two whole chromosomes had been literally shattered to pieces and stitched back together in a haphazard way – not so much shuffling the pages of the genetic recipe book as completely ripping them to pieces and randomly gluing the bits back together. The researchers call this “chromothripsis” – thripsis being Greek for “shattered into pieces”.

This didn’t seem to be a vanishingly rare event either. Two to three per cent of cancers studied by the team so far show the signs of chromothripsis (across a wide range of different cancer types). And in some cancer types it seemed to be even more common – for example, around a quarter of bone cancer samples had shattered chromosomes.

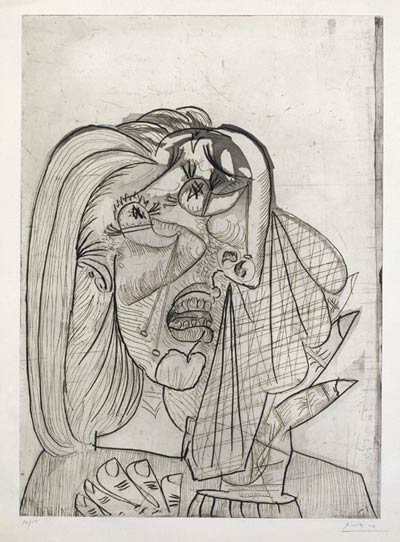

artwork { Pablo Picasso, Weeping Woman, 1937 }