Eyewitnesses say they are ordinary-looking people. Some say they appear to be in a kind of trance. Others describe them as being misshapen monsters. At this point, there’s no really authentic way for us to say who or what to look for and guard yourself against.

If you ask a person when “middle age” begins, the answer, not surprisingly, depends on the age of that respondent. American college-aged students are convinced that one fits soundly into the middle-age category at 35. For respondents who are actually 35, middle age is half a decade away, with 40 representing the inaugural year. (…) Recently, a large sample of Swiss participants spanning several generations agreed with one another that middle-aged people are those who are between 35 to 53 years of age.

However, the precise chronological point at which we formally enter “middle age” is of little importance. (…) We’ve all heard of the dreaded “midlife crisis,” but what, exactly, is it? Furthermore, does it even exist as a scientifically valid concept? (…)

“Midlife crisis” was coined by Elliott Jacques in 1965. (…) According to him, the midlife crisis is such a crisis that many great artists and thinkers don’t even survive it. (…) He decided to crunch the numbers with a “random sample” of 310 such geniuses and, indeed, he discovered that a considerable number of these formidable talents—including Mozart, Raphael, Chopin, Rimbaud, Purcell, and Baudelaire—succumbed to some kind of tragic fate or another and drew their last breaths between the ages of 35 and 39. “The closer one keeps to genius in the sample,” Jacques observes, “the more striking and clear-cut is this spiking of the death rate in midlife.” (…)

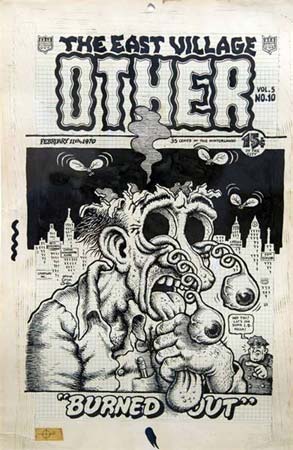

Basically, argues Jacques, around the age of 35, genius can go in one of three directions. If you’re like that last batch of folks, you either die, literally, or else you perish metaphorically, having exhausted your potential early on in a sort of frenzied, magnificent chaos, unable to create anything approximating your former genius. The second type of individual, however, actually requires the anxieties of middle age—specifically, the acute awareness that one’s life is, at least, already half over—to reach their full creative potential. (…) Finally, the third type of creative genius is prolific and accomplished even in their earlier years, but their aesthetic or style changes dramatically at middle age, usually for the better. (…)

The phrase “midlife crisis” didn’t really creep into suburban vernacular as a catchall diagnosis until the late 1970s. This is when Yale’s Daniel Levinson, building on the stage theory tradition of lifespan developmentalist Erik Erikson, began popularizing tales of middle-class, middle-aged men who were struggling with transitioning to a time where “one is no longer young and yet not quite old.”