What comes after once, twice, thrice? Nothing.

When Facebook goes public this year, it will raise at least $5 billion, making it the biggest Internet IPO the world has ever seen. The day it debuts on the stock exchange, Facebook will be worth more than General Motors, the New York Times Company, and Sprint Nextel combined. (…)

For roughly 65 years—say, from 1933 to 1998—the initial public offering was the engine of American capitalism. Entrepreneurs sold shares to investors and used the proceeds to build their young companies or invest in the future. After their IPOs, for instance, Apple and Microsoft had the necessary funds to develop the Macintosh and Windows. The stock market has been the most efficient and effective method of allocating capital that the world has ever seen.

That was a useful function, but it’s one that IPOs no longer serve. Going public is more difficult than it used to be—Sarbanes-Oxley regulations have made filing much more difficult, and today’s investors tend to shy away from Internet companies that don’t have a proven track record of steady profitability. That has created a catch-22: By the time a company can go public, it no longer needs the cash. Take Google. It had already been profitable for three years before raising $1.2 billion in its 2004 public offering. And Google never spent the money it raised that year. Instead, it put the cash straight into the bank, where the funds have been sitting ever since. Today, Google’s cash pile has grown to more than $44 billion.

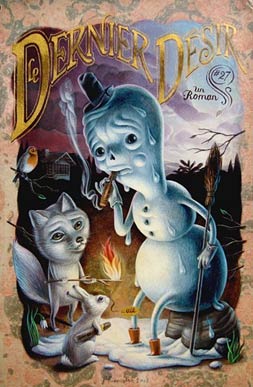

photo { Femke Hiemstra }