Incautiously I took your part when you were accused of pilfering. There’s a medium in all things. Play cricket.

You’re imagining, in the course of a game of make-believe, that you’re a cat. You don’t believe that you’re a cat. You are moved to say “Meow.” This case illustrates something that a theory of imagination should explain: sometimes when you imagine something, you are moved to act.

Consider another case. You’re watching a movie. A monster is on the loose and you are imagining, along with the movie, that it is at- tacking people willy-nilly. You do not believe there is a monster on the loose or that you are in any danger, but still you feel afraid. This case illustrates something else that a theory of imagination should explain: sometimes we have emotional reactions to things that we do not believe but merely imagine.

[…]

To be clearer, the first phenomenon we think needs accounting for is that sometimes you are moved to act by something you imagine but do not believe. Children are a good source of examples of this phe- nomenon — they act on the basis of their imaginings a lot. […]

Other, related questions that we try to answer are: How do imaginings motivate behavior? To what extent, and in what respects, is the behavior-generating role of imagination like the behavior-generating role of belief? Beliefs don’t generate behavior all on their own; they do so in combination with desires. If imaginings play something like the role of beliefs in generating behavior, is there also some state that plays something like the role of desire? If so, what kind of state is it — a desire, or something else? And if it’s a desire, a desire about what?

{ Tyler Doggett & Andy Egan, The Case for an Imaginative Analogue of Desire, 2007 | PDF }

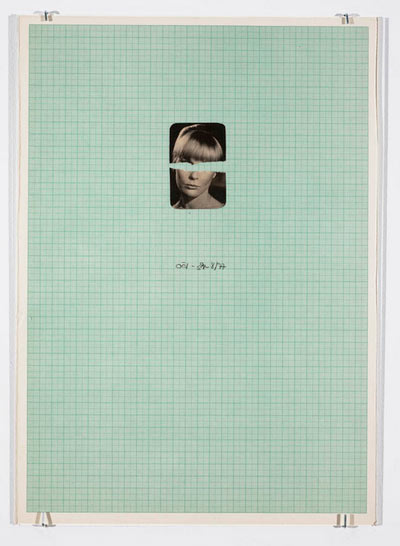

image { Jiří Kovanda }