The idea of nostalgia as a disruption of time

Memories merge into memories. Byatt’s grandmother’s vivid remembering becomes the granddaughter’s vivid imagining. Who can tell the difference? In time, we might become so convinced by other people’s descriptions of their memories that we start to claim them as our own. If the experimental conditions are set up correctly, it turns out to be rather simple to give people memories for events they never actually experienced.

A well-known series of experiments by the American cognitive psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues at the University of Washington has shown that presenting participants with misleading information after they have experienced an event can change their memory of the event. […]

A recent neuroimaging study has provided some of the first clues to the neural mechanisms involved when our memories are shaped by other people. […] The scan findings showed that persistent memory errors, which went on to become part of the subjects’ own retelling of the story, were associated with greater activation in the hippocampus (the brain region primarily responsible for laying down episodic memories) than transient errors, which seemed to be more about conforming to a public account of the events. The researchers also showed that the amygdala (a part of the brain responsible for emotional memory) was particularly active when the participants thought that the information had come from other people, as compared with computer-generated representations. They suggested that the amygdala, so closely connected to the hippocampus, may play a specific role in the process by which social influences shape our memories. […]

A team of British researchers recently conducted the first scientific study of “nonbelieved memories”: memories which people cease to believe after coming to realise that they are false.

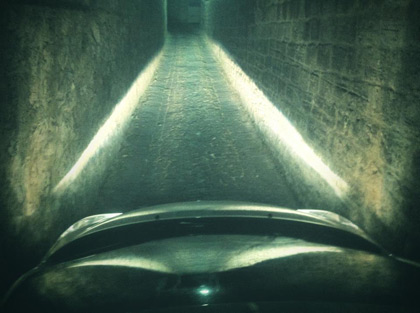

photo { Tim Geoghegan }