Uh-oh, love comes to town

Optimists called the first world war “the war to end all wars”. Philosopher George Santayana demurred. In its aftermath he declared: “Only the dead have seen the end of war”. History has proved him right, of course. What’s more, today virtually nobody believes that humankind will ever transcend the violence and bloodshed of warfare. I know this because for years I have conducted numerous surveys asking people if they think war is inevitable. Whether male or female, liberal or conservative, old or young, most people believe it is. For example, when I asked students at my university “Will humans ever stop fighting wars?” more than 90 per cent answered “No”. Many justified their assertion by adding that war is “part of human nature” or “in our genes”. But is it really? (…)

A growing number of experts are now arguing that the urge to wage war is not innate, and that humanity is already moving in a direction that could make war a thing of the past.

Among the revisionists are anthropologists Carolyn and Melvin Ember from Yale University, who argue that biology alone cannot explain documented patterns of warfare. They oversee the Human Relations Area Files, a database of information on some 360 cultures, past and present. More than nine-tenths of these societies have engaged in warfare, but some fight constantly, others rarely, and a few have never been observed fighting. “There is variation in the frequency of warfare when you look around the world at any given time,” says Melvin Ember. “That suggests to me that we are not dealing with genes or a biological propensity.” (…)

Brian Ferguson of Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, also believes that there is nothing in the fossil or archaeological record supporting the claim that our ancestors have been waging war against each other for hundreds of thousands, let alone millions, of years.

War emerged when humans shifted from a nomadic existence to a settled one and was commonly tied to agriculture, Ferguson says. “With a vested interest in their lands, food stores and especially rich fishing sites, people could no longer walk away from trouble.” What’s more, with settlement came the production of surplus crops and the acquisition of precious and symbolic objects through trade. All of a sudden, people had far more to lose, and to fight over, than their hunter-gatherer forebears. (…)

Perhaps the best and most surprising news to emerge from research on warfare is that humanity as a whole is much less violent than it used to be (see our timeline of weapons technology). People in modern societies are far less likely to die in battle than those in traditional cultures. For example, the first and second world wars and all the other horrific conflicts of the 20th century resulted in the deaths of fewer than 3 per cent of the global population. According to Lawrence Keeley of the University of Illinois in Chicago, that is an order of magnitude less than the proportion of violent death for males in typical pre-state societies, whose weapons consist only of clubs, spears and arrows rather than machine guns and bombs.

There have been relatively few international wars since the second world war, and no wars between developed nations. Most conflicts now consist of guerilla wars, insurgencies and terrorism - or what the political scientist John Mueller of Ohio State University in Columbus calls the “remnants of war”. He notes that democracies rarely, if ever, vote to wage war against each other, and attributes the decline of warfare over the past 50 years, at least in part, to a surge in the number of democracies around the world - from 20 to almost 100.

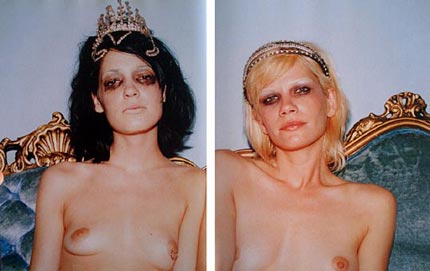

photo { Terry Richardson, Nikki and Zoe, 1995 }