A psychology study from Hong Kong suggests that, among men, the impulses to make love and war are deeply intertwined.

In a 2002 book, Chris Hedges compellingly argued that war is both an addiction and a way of engaging in the sort of heroic struggle that gives our lives meaning.

Evolutionary psychologists, on the other hand, see war as an extension of mating-related male aggression. They argue men compete for status and resources in an attempt to attract women and produce offspring, thereby passing on their genes to another generation. This competition takes many forms, including violence and aggression against other males — an impulse frowned upon by modern society but one that can be channeled into acceptability when one joins the military.

It’s an interesting and well-thought-out theory, but there’s not a lot of direct evidence to back it up. That’s what makes “The Face That Launched a Thousand Ships,” a paper just published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, so intriguing.

A team of Hong Kong-based researchers led by psychologist Lei Chang of Chinese University conducted four experiments that suggest a link between the motivation to mate and a man’s interest in, or support for, war.

{ Miller-McCune | Continue reading }

relationships, science |

May 3rd, 2011

There are (at least) two ways to implement a (Star Trek style) transporter:

1. A space-time wormhole takes you “directly” from here to there, or

2. We scan you, send the info, make a new copy at the other end, and destroy the original.

Some people care greatly about transporter type; they’d pay to use type #1, but pay greatly to avoid using type #2. But regardless of the morality of a type #2 transporter, I’m pretty confident that if cheap type #2 transporters were available, but not type #1, many people would use them often. (…)

A similar relation applies to two types of super-watches. (…) Here are the two ways to make super-watches:

1. Time Machine + Memory Wipe: The second time you push the button you enter a time machine that brings you back to soon after the moment you first pushed the button, displaced by a few feet. It also erases all memories you might have acquired since the first time you pushed the button. And no, you can’t bring anything else with you in the time machine.

2. Limited Time Copier: When you turn on the watch it makes an exact copy of you and puts that copy a few feet away. When you turn the watch off, or it automatically turns off, you are destroyed.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

ideas, time |

May 2nd, 2011

Almost every country in the EU last week approved the use of Meat Glue in food. Technically called thrombian, or transglutaminase (TG), it is an enzyme that food processors use to hold different kinds of meat together.

Imitation crab meat is one of the more common applications: it’s made from surimi, a “fish-based food product” made by pulverizing white fish like pollock or hake into a paste, which is then mixed with meat glue so that the shreds stick together and hold the shape wanted for it by its creator.

Chicken nuggets are also often bound with meat glue, as are meat mixtures meant to mold like sausage but without the casing. Meat glue is also used by high-end chefs like New York restaurant WD-50’s Wylie Dufresne, who is famous for his shrimp pasta dish—instead of shrimp with pasta, he just makes the pasta out of shrimp.

{ Discovery | Continue reading }

economics, food, drinks, restaurants, gross |

May 2nd, 2011

When we think of demographics that are easily distracted, we tend to think of younger generations, people on their phones over dinner or texting while driving, or only listening to you with one ear while they listen to their ipod with the other. But when we’re talking about cognitive tasks like working memory, the ability to work without distractions is actually highest when you’re younger, and decreases with age. Working memory is the ability to store bits of information and manipulate them over a short period of time. How long the working memory lasts for depends on what you’re trying to remember (say, a string of words that makes sense over a string of numbers that doesn’t), the amount of information you’re trying to process, and on how distracted you are.

{ Neurotic Physiology | Continue reading }

memory, neurosciences |

May 2nd, 2011

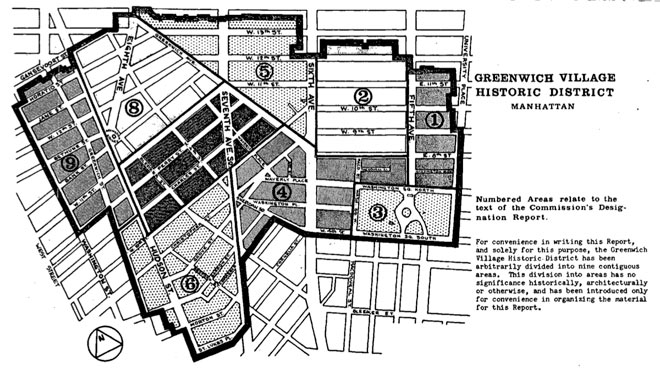

Recently, scientists have begun to focus on how architecture and design can influence our moods, thoughts and health. They’ve discovered that everything—from the quality of a view to the height of a ceiling, from the wall color to the furniture—shapes how we think. (…)

In 2009, psychologists at the University of British Columbia studied how the color of a background—say, the shade of an interior wall—affects performance on a variety of mental tasks. They tested 600 subjects when surrounded by red, blue or neutral colors—in both real and virtual environments.

The differences were striking. Test-takers in the red environments, were much better at skills that required accuracy and attention to detail, such as catching spelling mistakes or keeping random numbers in short-term memory.

Though people in the blue group performed worse on short-term memory tasks, they did far better on tasks requiring some imagination, such as coming up with creative uses for a brick or designing a children’s toy. In fact, subjects in the blue environment generated twice as many “creative outputs” as subjects in the red one.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

architecture, colors, psychology |

May 2nd, 2011

Negotiations trigger anxiety. Across four studies, we demonstrate that anxiety is harmful to negotiator performance.

Compared to negotiators experiencing neutral feelings, negotiators who feel anxious expect lower outcomes, make lower first offers, respond more quickly to offers, exit bargaining situations earlier, and ultimately obtain worse outcomes.

{ Science Direct | Continue reading }

economics, guide, psychology |

May 1st, 2011

…to recognize that we now live in a different, more constrained world in which prices of raw materials will rise and shortages will be common.

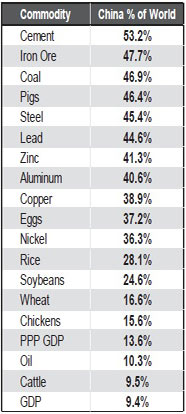

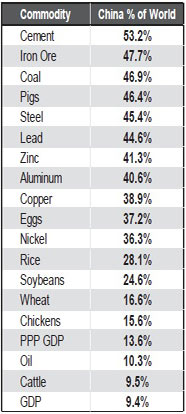

Accelerated demand from developing countries, especially China, has caused an unprecedented shift in the price structure of resources: after 100 years or more of price declines, they are now rising, and in the last 8 years have undone, remarkably, the effects of the last 100-year decline. (…)

The primary cause of this change is not just the accelerated size and growth of China, but also its astonishingly high percentage of capital spending, which is over 50% of GDP, a level never before reached by any economy in history, and by a wide margin. Yes, it was aided and abetted by India and most other emerging countries, but still it is remarkable how large a percentage of some commodities China was taking by 2009. Exhibit 3 shows that among important non-agricultural commodities, China takes a relatively small fraction of the world’s oil, using a little over 10%, which is about in line with its share of GDP (adjusted for purchasing parity). The next lowest is nickel at 36%. The other eight, including cement, coal, and iron ore, rise to around an astonishing 50%! In agricultural commodities, the numbers are more varied and generally lower: 17% of the world’s wheat, 25% of the soybeans, 28% of the rice, and 46% of the pigs.

{ Business Insider | Continue reading }

asia, economics |

May 1st, 2011

The sorites paradox (from Ancient Greek: sōreitēs, meaning “heaped up”) is a paradox that arises from vague predicates.

The paradox of the heap is an example of this paradox which arises when one considers a heap of sand, from which grains are individually removed.

Is it still a heap when only one grain remains?

If not, when did it change from a heap to a non-heap?

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Christian Chaize }

Linguistics, ideas |

May 1st, 2011

If there’s one topic likely to generate spit-flecked ire, it is the controversy over the potential health threat posed by cell phone signals.

That debate is likely to flare following the publication today of some new ideas on this topic from Bill Bruno, a theoretical biologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

The big question is whether signals from cell phones or cell phone towers can damage biological tissue.

On the one hand, there is a substantial body of evidence in which cell phone signals have supposedly influenced human health and behavior. The list of symptoms includes depression, sleep loss, changes in brain metabolism, headaches and so on.

On the other hand, there is a substantial body of epidemiological evidence that finds no connection between adverse health effects and cell phone exposure.

What’s more, physicists point out that the radiation emitted by cell phones cannot damage biological tissue because microwave photons do not have enough energy to break chemical bonds.

The absence of a mechanism that can do damage means that microwave photons must be safe, they say.

That’s been a powerful argument. Until now.

Today, Bruno points out that there is another way in which photons could damage biological tissue, which has not yet been accounted for.

He argues that the traditional argument only applies when the number of photons is less than one in a volume of space equivalent to a cubic wavelength.

When the density of photons is higher than this, other effects can come into play because photons can interfere constructively.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

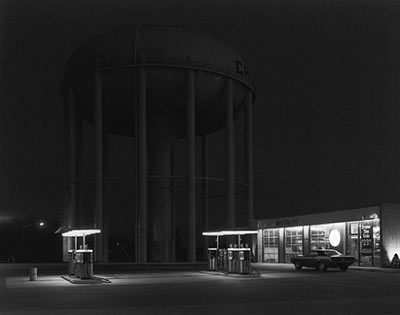

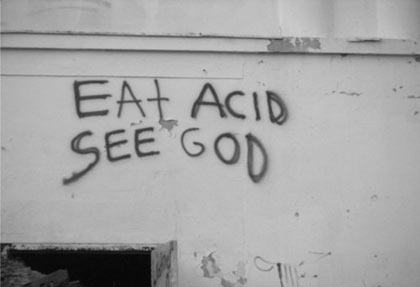

photo { George Tice }

controversy, health, technology |

May 1st, 2011

In a notification sent to all service providers and hosting companies in Turkey on Thursday (28 April), the Telecommunication Communication Presidency (TİB) forwarded a list of banned words and terms. (…)

[Some of the banned words:] Adrianne, Animal, Sister-in-law, Blond, Beat, Enlarger, Nude, Crispy, Escort, Skirt, Fire, Girl, Free, Gay, Homemade, Liseli (’high school student’).

{ Bianet | Continue reading }

Linguistics, law |

May 1st, 2011

{ Kill Devil Hills is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, USA. Nearby Kitty Hawk is frequently cited as the location of the Wright brothers‘ first controlled, powered airplane flights on December 17, 1903. The flights actually occurred in Kill Devil Hills. | Wikipedia | Continue reading Photo: First flight of the Wright Flyer I, December 17, 1903, Orville piloting, Wilbur running at wingtip. }

U.S., airports and planes, flashback |

May 1st, 2011

In a relationship, who do you think is more likely to say “I love you” first – men or women?

In a recent study, 64% of participants were likely to think women were the first to say they were in love, and these professions were estimated to occur close to 2 months into a relationship. The stereotype is that women are more interested in relationships, especially serious relationships, and are therefore more likely to confess their feelings sooner than men.

When looking at actual relationships, however, men were more likely to profess their feelings first. 62% of participants reporting on past relationships and 70% reporting on current relationships stated that the man said “I love you” first. On average, men started thinking about professing their love about 3 months into the relationship whereas women in the study started thinking about it closer to 5 months into the relationship.

{ eHarmony | Continue reading }

photo { Eric Antoine }

relationships |

April 29th, 2011

Let’s consider the butterfly. One of the most taxing movements in sports, the butterfly requires greater energy than bicycling at 14 miles per hour, running a 10-minute mile, playing competitive basketball or carrying furniture upstairs. It burns more calories, demands larger doses of oxygen and elicits more fatigue than those other activities, meaning that over time it should increase a swimmer’s endurance and contribute to weight control.

So is the butterfly the best single exercise that there is? Well, no. The butterfly “would probably get my vote for the worst” exercise, said Greg Whyte, a professor of sport and exercise science. (…)

Ask a dozen physiologists which exercise is best, and you’ll get a dozen wildly divergent replies. (…)

Sticking with an exercise is key, even if you don’t spend a lot of time working out. The majority of the mortality-related benefits from exercising are due to the first 30 minutes of exercise. A recent meta-analysis of studies about exercise and mortality showed that, in general, a sedentary person’s risk of dying prematurely from any cause plummeted by nearly 20 percent if he or she began brisk walking (or the equivalent) for 30 minutes five times a week. If he or she tripled that amount, for instance, to 90 minutes of exercise four or five times a week, his or her risk of premature death dropped by only another 4 percent. So the one indisputable aspect of the single best exercise is that it be sustainable. From there, though, the debate grows heated.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { Indlekofer and Knoepfel }

guide, health, sport |

April 29th, 2011

This study sets out to focus on the nature of changes some major interjections have gone through. (…)

Historically, interjections have been regarded as marginal to language. Latin grammarians described them as non-words, independent of syntax, signifying only feelings or states of mind. Nineteenth-century linguists regarded them as paralinguistic, even non-linguistic phenomena. (…)

Traditional classification of interjections to primary and secondary might help us to narrow down our focus. In keeping with this classification, the words from other word classes (e.g., hell, boy, and Jesus), when used as interjections, construct the category of secondary interjections, and all the other interjections that have already appeared in the dictionary such as wow, oops, ouch, yuck, and whoa form the primary group. The latter interjections are, in point of fact, emotion-expressive so much so that they cannot be expressed by means of other words or phrases.

{ I Will Wow You! Pragmatic Interjections Revisited | Studies in Literature and language | Continue reading | PDF }

Is it true “W” can be used as a vowel?

Sure. Try “how,” which is phonetically equivalent to “hou,” as in house.

{ The Straight Dope | Continue reading }

Linguistics |

April 29th, 2011

Brazilian man has claimed his wife attempted to kill him by putting poison into her vagina and inviting him to drink from the furry cup.

Brazilian man has claimed his wife attempted to kill him by putting poison into her vagina and inviting him to drink from the furry cup.

Man arrested for singing ‘Kung Fu Fighting.’ Police arrested the singer on racism charges after a man reportedly of Chinese descent complained about his performance of the song.

California gangster’s tattoo of crime scene helps solve murder.

Student yawned so hard during lecture that she couldn’t close her mouth. Holly was taken to Northampton General Hospital where her jaw was eventually freed by forcing 26 wooden splints in her mouth.

Psychologists warn that therapies based on positive emotions may not work for Asians.

Man dressed as cow crawled into a Walmart on all fours and stole 26 Gallons of Milk.

People who overuse credit believe products have unrealistic properties.

A study at a US Buddhist retreat suggests eastern relaxation techniques can protect our chromosomes from degenerating.

The Cognitive System Theory introduced here provides the first fully scientific model of how the hominid brain works, and explains how its two masterstrokes of cognitive development are achieved for each and every one of us in childhood.

Authors compare the frequency of swear words in London teens to the same from an earlier study in East Coast American adolescents.

Investigating behavioural mimicry in the context of stair/escalator choice.

A study discovered that birds which are able to breed in the city center tend to have larger brains.

Researchers at Queen’s University have found a strong association between computer and Internet use in adolescents and engagement in multiple-risk behaviors, including illicit drug use, drunkenness and unprotected sex.

Drinking energy beverages mixed with alcohol may be riskier than drinking alcohol alone.

The brain regions responsible for what might be considered “willpower” show more activity in those who have quit smoking.

Even without symptoms, genital herpes can spread.

Engineering researchers at the University of Southern California have made a significant breakthrough in the use of nanotechnologies for the construction of a synthetic brain. They have built a carbon nanotube synapse circuit whose behavior in tests reproduces the function of a neuron, the building block of the brain.

A new kind of plastic that can repair itself when exposed to ordinary light has been unveiled by scientists in the U.S. for the first time.

Carnegie Mellon researchers build time machine to visually explore space and time.

Carnegie Mellon researchers build time machine to visually explore space and time.

More than 30 years after they left Earth, NASA’s twin Voyager probes are now at the edge of the solar system.

Can a complete novice become a golf pro with 10,000 hours of practice?

“Can we get the public to think of porn as something that they’re willing to pay for again? We’ll see.” A Denton lawyer devotes his life to fighting America’s porn thiefs.

When you buy an iPhone app, AT&T gets nothing. When you buy an Android app, Verizon gets a cut.

A Contrarian View of Copyright: Hip-Hop, Sampling, and Semiotic Democracy.

The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany.

Why do we say a “pair of pants” when there’s only one of them?

Shit-faced: a brief history of the word.

Interview With a Trading Legend. (A thirty-year track record (audited) of 41.6% compound returns.)

He’s built a career concocting high-concept fragrances like “Wet Mitten” and “Clean Baby Butt.” Now Christopher Brosius is attempting his next olfactory experiment: creating a perfume you can’t even smell.

The officers were on a training mission, exploring the 4.3 miles of catacombs that twist beneath the 16th arrondissement of Paris. They found 3,000 square feet of subterranean galleries, strung with lights, wired for phones, live with pirated electricity, uncovered a bar, lounge, workshop, dining corner and small screening area.

Sagrada Familia: Gaudí’s cathedral is nearly done, but would he have liked it?

Why is there so many violent crime at fast-food restaurants?

Like all of the other water bodies in Central Park, Turtle Pond is man-made – filled with New York City drinking water. However, you wouldn’t want to drink this water, since it’s filled with five kinds of turtles who live in the Pond year round. Many of these turtles started out as pets in city apartments, but eventually outgrew their urban accommodations, and were brought to the Park by their former owners.

Why do New Yorkers wear so much black?

This is a recording of Allen Ginsberg reading his poem, “America” over Tom Waits’s “Closing Time.” Listen to it naked.

Does every other movie lately seem to have a shot of the leading man casually walking away from a vehicle he’s just blown up?

There’s a form of neurotoxic honey, genuinely known as “mad honey,” created by bees taking nectar from the rhododendron ponticum flower.

Four Nasty Conditions Bad Sunglasses Could Give You.

Four Nasty Conditions Bad Sunglasses Could Give You.

11 Grammatically Incorrect Movie Titles.

CMYK: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key.

Unicorn in real life. [videos]

Sperm retrievial machine via China and Sperm Bank ATM.

Probably the first time breast groping has been used in a political poster.

The lion was a gift, but after it died, the pelt and bones were presented to a taxidermist who had never seen a lion.

Meanwhile, on the BBC.

every day the same again |

April 29th, 2011

“It is a surprise that a jellyfish — an animal normally considered to be lacking both brain and advanced behavior — is able to perform visually guided navigation, which is not a trivial behavioral task,” said lead researcher Anders Garm of the University of Copenhagen. (…)

Box jellyfish have 24 eyes of four different types, and two of them — the upper and lower lens eyes — can form images and resemble the eyes of vertebrates like humans. The other eyes are more primitive. It was already known that box jellyfish’s vision allows them to perform simpler tasks, like responding to light and avoiding obstacles.

In the new study, scientists found that one species of the cube-shaped box jellyfish, Tripedalia cystophora, uses its upper lens eyes, which are mounted on four cuplike structures, to make sure it stays close to the prop roots of mangrove trees that define its habitat.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading | Neurophilosophy }

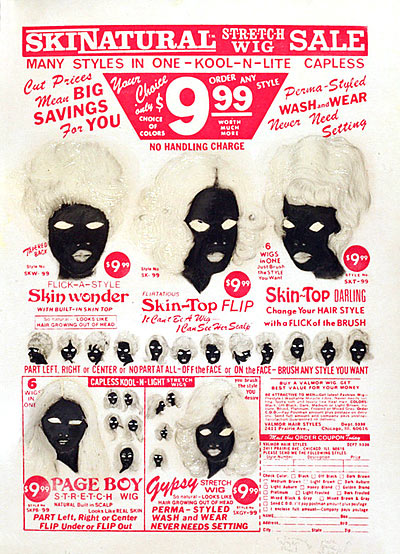

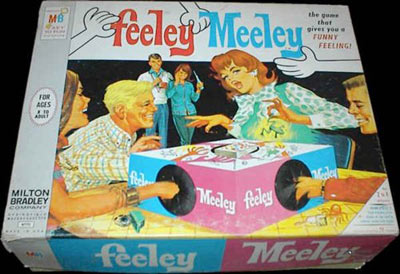

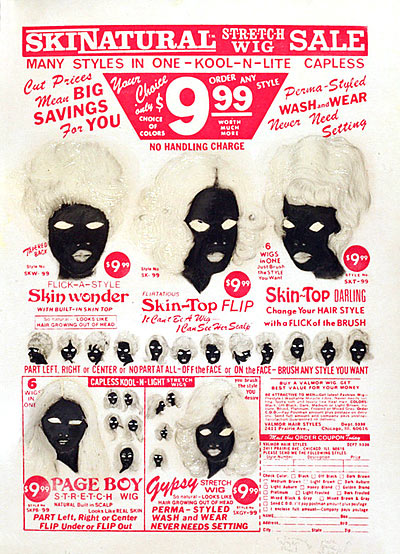

artwork { Ellen Gallagher, DeLuxe, 2004–05 [detail] | currently on view at the MoMA, NYC }

eyes, jellyfish |

April 28th, 2011

Scientists have untangled some — but not nearly all — of the mysteries behind our love and hatred of certain foods. (…)

Our tongues perceive only five basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and “umami,” the Japanese word for savory. (…)

“We as primates are born liking sweet and disliking bitter,” said Marcia Pelchat, who studies food preferences at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. The theory is that we’re hard-wired to like and dislike certain basic tastes so that the mouth can act as the body’s gatekeeper.

Sweet means energy; sour means not ripe yet. Savory means food may contain protein. Bitter means caution, as many poisons are bitter. Salty means sodium, a necessary ingredient for several functions in our bodies. (By the way, those tongue maps that show taste buds clumped into zones that detect sweet, bitter, etc.? Very misleading. Taste receptors of all types blanket our tongues — except for the center line — and some reside elsewhere in our mouths and throats.)

Researchers have found only one major human gene that detects sweet tastes, but we all have it. By contrast, 25 or more bitter receptor genes may exist, but combinations vary by person. Some genetic connections are so strong that scientists can predict fairly accurately how people will react to certain bitter tastes by looking at their DNA.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, genes, science |

April 28th, 2011

A new study finds that when a ball appears to magically change size in front of their eyes, female dogs notice but males don’t. The researchers aren’t sure what’s behind the disparity, but experts say the finding supports the idea that—in some situations—male dogs trust their noses, whereas females trust their eyes.

{ Science magazine | Continue reading }

photos { Eylül Aslan }

dogs, science |

April 28th, 2011