The deva asked, What causes ruin in the world?

One of the mysteries of human behavior is why we sometimes act with completely selfless altruism. When asked to play totally anonymous games in which we can cheat without anyone else ever finding out, very often we don’t.

Instead, we play the game fairly, which results in a cost to ourselves (compared with what we could’ve had) and a benefit to the stranger. That’s a mystery because evolution says that organisms which don’t act to maximize benefit to themselves - whatever the cost to others - should die out.

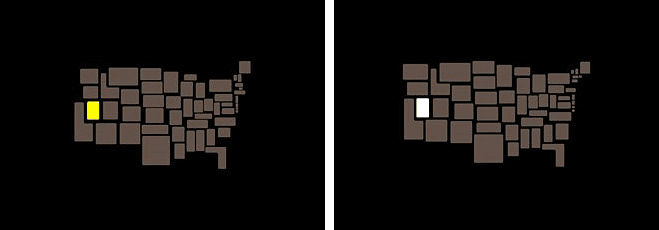

Several explanations have been put forward, but one of the most intriguing stems from the fact that we live in social networks. In a network like this, we depend critically on the kindness of others.

A new study has looked at how altruistic behavior can be transmitted between players in the kinds of anonymous games that social psychologists are so fond of.

What they found was that the amount individuals contributed in one round was affected by how generous their partners were in previous rounds. If they played with generous people in round 1, then they would be more generous to the new partners they had in round 2. In fact, they showed that this effect was propagated through new partners.

Unselfish acts propagated out to 3 degrees of separation. When you remember that only 6 degrees of separation stand between you and every other person on the planet, you can understand how powerful and important this effect is.

{ Epiphenom | Continue reading }

Most people with an interest in evolution understand why selfish genes do not mean selfish individuals. It’s clear that selfish genes will benefit from co-operation (you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours, also known as reciprocity), and kin selection (as the biologist JBS Haldane famously put it, “I would lay down my life for two brothers or eight cousins”).

What most people may not know (I certainly didn’t before reading West’s article) is that these, in fact, are the sole genetic basis for altruism. But if that’s the case, how do you get from here to the apparently completely selfless altruism sometimes seen in humans?

Reciprocity doesn’t need to be direct to be effective. If, by sharing with you I help to set up a virtuous circle, that will likely result in some benefit to me down the line. This has been seen in practice, with virtuous deeds propagating out to at least three degrees of separation.

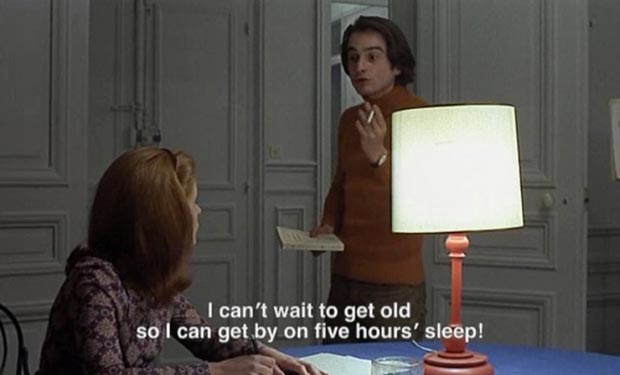

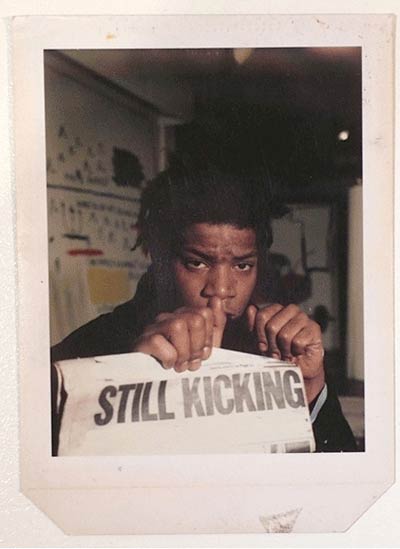

photo { Noah Kalina }