And it’s either feast or famine, I’ve found out that it’s true

The Prime Minister of Japan recently stated that his nation was facing its worst crisis since World War II. While most of the world is focused on tragic images of floodwater and rubble, and fixated on radiation levels, there is a bigger picture to be examined – one that also includes energy, coal and the Strait of Hormuz.

The geography of the Persian Gulf is extraordinary. It is a narrow body of water opening into a narrow channel through the Strait of Hormuz. Any diminution of the flow from any source in the region, let alone the complete closure of the Strait of Hormuz, would have profound implications for the global economy.

For Japan it could mean more than higher prices. It could mean being unable to secure the amount of oil needed at any price. The movement of tankers, the limits on port facilities and long-term contracts that commit oil to other places could make it impossible for Japan to physically secure the oil it needs to run its industrial plant. On an extended basis, this would draw down reserves and constrain Japan’s economy dramatically. And, obviously, when the world’s third-largest industrial plant drastically slows, the impact on the global supply chain is both dramatic and complex.

{ George Friedman | Continue reading }

Nuclear plants in France, Germany, and the U.S. are far more automated than in Japan, where more controls are based on manual decisions, switches, and reactions, says Roger Gale, a nuclear industry consultant and former official at the U.S. Department of Energy who served as a consultant to Tepco for 20 years. He thinks U.S. utilities would have acted more quickly in a similar disaster. “[Tepco] probably reacted more slowly in the initial case than they needed to.”

Gale says a culture of complacency within Tepco may also have contributed to the crisis. Tepco has massive cash flows and a reputation for hiring the best and brightest engineers in Japan. However, Gale says, an array of management problems–a lack of transparency, problems with record keeping, relying on manual rather than automatic controls, and being slow on the draw when making decisions—plague the organization.

{ Fast Company | Continue reading }

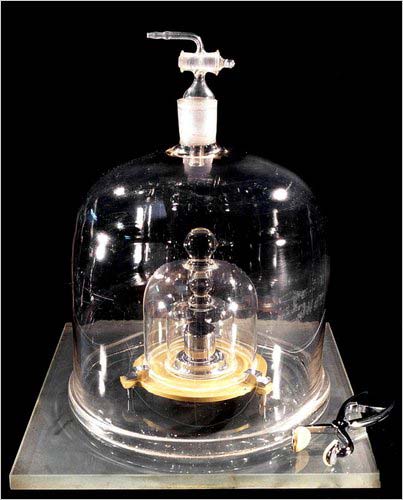

At this point in the Japanese nuclear emergency it is coming down to the simple proposition of how do you drop enough water on the stricken reactors, and especially the spent fuel ponds, to keep further damage from happening?

{ Robert X. Cringely | Continue reading | And: Japan Takes Extraordinary Measures to Cool Nuclear Plant }

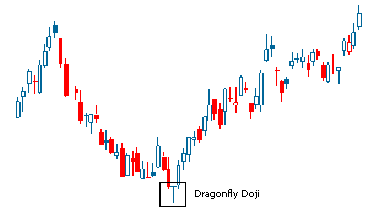

related { CNN/Money jumps on the fear bandwagon with this interactive graphic }